Events like the 1969 Manson murders will always fascinate audiences, says Richard Dale

The question comes from a film-maker: “How do you decide what you want to make a film about?”

I’m speaking on a lecture tour in China. I look at my credits on the projector and feel something of a fraud. A D-Day film, a Twin Towers film, one about Princess Diana. Hardly stories unearthed by a journalistic genius.

I’ve got two films in my mind this month: the re-release of my 2009 movie Moonshot, starring Andrew Lincoln, and a new two-part series for ITV: Manson – The Lost Tapes.

Both are stories from 1969, both are among the most obvious subjects from the past 50 years, and both have been jumped upon by outlets looking for stories for primetime in 2018. It seems there’s an appetite for old stories. Why?

Partly, I believe, it is because these are familiar stories. They are the landmarks in our lives – the things we navigate by. Where were you on 9/11 or when Princess Diana died? These events are what JFK’s assassination or Apollo 11 were to our parents.

If I knew what the stories would be for our children’s generation, I’d be pitching them. One thing I am sure of is they will be world stories – big, transnational events that link people together.

There’s something else world stories like these have in common: they are, in some ways, still ‘alive’. One of my first jobs as a director was with theatre legend Peter Brook. He is known as the ‘best director the National Theatre never had’ – I knew him for making the film version of Lord Of The Flies, which I’d watched at school.

I asked him why he hadn’t made more films and he said that, unlike theatre, film doesn’t have an internal life – it is, he continued, dead inside. I know what he means – to be alive, film needs to provoke a reaction, make you think and show you different ways of being. How can an old film do that?

“I don’t want films to be about the facts, but about the feel. How did it feel to be there – to be a part of it?”

The secret lies in how you tell these stories. Historical stories are rooted in fact, but they’re not about facts. Apart from anything else, many of those involved have a different set of ‘facts’ they’re absolutely convinced are true. And people who tune into films largely know the facts already.

I don’t want films to be about the facts, but about the feel. How did it feel to be there – to be a part of it? What would it be like if it had been me? How would I have measured up?

At the beginning of the year, I got a call from Naked TV chief exec Simon Andreae. He’d been chasing a unique archive of material filmed within Charles Manson’s cult, beginning just after the killing spree that shocked the world – when cult members murdered actress Sharon Tate, who was eight months pregnant at the time.

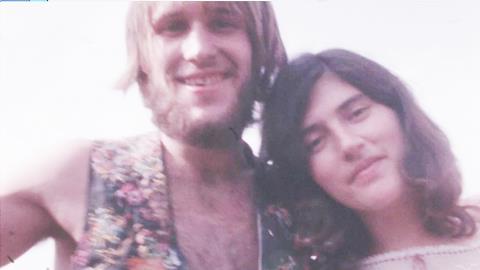

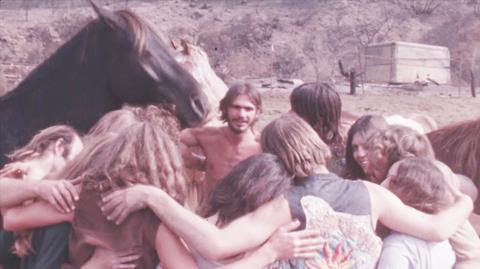

It had taken Simon two years and a private investigator to get hold of the footage, but he had it – and a new film transfer had brought the faces of the young people involved to life, like Kodachrome pictures of summers past. My good friend and fellow director Hugh Ballantyne had also put together some telling testimony from cult members willing to speak.

Mass murderers are really not my thing, but retelling this particular story seems to me to be different. It’s not really about Manson, it’s about us. What is it that made the young people in these intimate, loving pictures – people who really do begin just like us – do the most terrible things you can imagine?

Well-worn stories, well told afresh, unite us. They remind us what we have in common – in our lifetimes and in our capabilities as humans, for good and for ill.

In my pair of 1969 stories, we see the heights people can reach when we work together – and the depths that we plumb if all that concerns us is ourselves.

Richard Dale is writer and director of ITV and Fox series Manson – The Lost Tapes, which debuted on ITV on 27 September

No comments yet