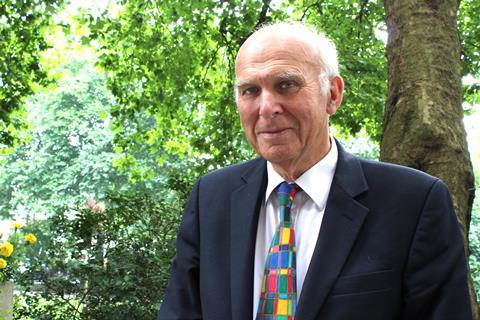

Government must include the industry in any transitional agreement, says Vince Cable

Watching developments on the news and listening to analysis on the radio, it is clear that Brexit will affect every industry and sector, including broadcasting.

Britain has an unparalleled history of broadcasting and our output has an enviable global reputation. Our creative industries contribute around £87bn a year to the economy – nearly £10m an hour – and account for around one in 11 jobs. The sector is growing at around 6% a year – three times faster than the economy at large.

The UK’s soft power – as the EU’s biggest broadcasting hub – is formidable. The Chinese love Sherlock and Blue Planet II, while Downton Abbey is a global phenomenon that has become a cultural touchstone referenced in everything from Family Guy and How I Met Your Mother to Iron Man.

Brexit jeopardises the potential of broadcasting, one of our most successful sectors, to prosper even further.

Highly skilled EU citizens make up as much as 40% of the UK creative sector’s workforce. This is one of the many reasons why an agreement must be made on the status of EU workers, and flexibility enshrined in the new system to allow broadcasters to continue to recruit EU citizens as freelancers when required.

The industry is heavily reliant on freelance workers, both in front of and behind the camera. The transition to new arrangements in March 2019 must be seamless and encompass the current A1 certificate system.

But it’s not just individuals who will be affected. Commercial and public service broadcasters alike are warning of the threats to their income, as are production companies.

”If we end up with an EU trade deal with tariff barriers – or, worse, crash out with no deal – TV producers could face losses of more than £8.2bn”

BBC Worldwide generates hundreds of millions of pounds of revenue from EU markets, which in turn is reinvested into UK public service content. The Commercial Broadcasters Association estimates that 25% of UK broadcasting jobs are, in part or exclusively, with international channels.

If we end up with an EU trade deal with tariff barriers and licensing restrictions – or, worse still, crash out with no deal – TV producers could face losses of more than £8.2bn, as well as reduced broadcast content.

One of the many ironies of the Brexit process is that Britain was leading the efforts to create a Digital Single Market with common rules on data protection, consumer protection and copyright. There are already established elements of this model that we must retain.

The ‘country of origin’ principle allows media channels across the EU to be regulated in just one member state. For example, a third of the 1,200 television services regulated by Ofcom are never seen by UK viewers, but are broadcast across the EU.

Conversely, there are 35 channels, including Netflix, that transmit to UK viewers but are licensed in other EU countries. UK content is therefore EU content, but would face sales limitations if banded outside EU quotas. Agreement on the country of origin principle is a priority in the negotiations.

The government’s refusal to admit that there are problems, or to publish the sector impact assessments that Brexit secretary David Davis alluded to and then denied the existence of, is absurd. We must see what these studies say about creative industries.

The bottom line is that the government cannot, in less than 18 months, manage the whole transfer of a broadcast operation from one jurisdiction to another.

Broadcasting must, therefore, be part of any transitional agreement from March 2019, and of any free trade deal – if, indeed, one can be negotiated.

Vince Cable is leader of the Liberal Democrats and was secretary of state for Business, Innovation and Skills from 2010 to 2015

4 Readers' comments