The co-creator of Humans felt his horizons expanded by the sci-fi show’s unlimited belief in human potential

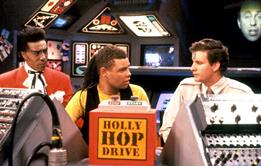

Star Trek: the Next Generation

Paramount, 1987-1994

UK tx: BBC2

I doubt I’m fully conscious of my deepest, truest influences. In truth, Thundercats is the show that ‘shaped’ me as it led me to comics, which led me to films and TV.

I’m much better at identifying what I’d like to be influenced by. I hold the dull opinion that The Wire is the best show ever made. I hope I’m influenced by it, but I suspect I’m just overawed.

The early spec TV scripts that my writing partner Jon Brackley and I submitted are naked Joss Whedon pastiches. Peep Show is my favourite comedy of all time, as it feels like it was made just for me.

But the show that hogs the most space in the middle of that Venn diagram is Star Trek: The Next Generation.

I can still feel my horizons expanding as watched it. All science fiction fans want to be transported, to be beamed into mind-bending worlds of discovery and wonder - but what TNG found again and again at the edge of space was a sophisticated, hopeful, philosophical exploration of what humanity was, or could be.

From a writer’s point of view, the miracle of TNG was that the characters were usually of one mind, professionally and personally dedicated to each other - and to the non-interventionist, post-capitalist, egalitarian ideals of the utopian Federation.

The conflict between the crew had to be found in subtle differences of moral position, as they tried to apply their 24th century values to unique new problems - usually posed by actors giving fantastic, theatrical, utterly sincere performances under latex foreheads and a couple of coats of matt emulsion. The narrative resolutions arrived at were generous, imaginative, cerebral and nuanced.

Point me to a bit of TV with a grander imagination or generosity of spirit than The Inner Light, where Picard lives an entire life in an instant.

It’s fascinating to chart in subsequent Trek shows the rise of the interpersonal conflict TNG avoided (at creator Gene Roddenberry’s express instruction). Characters increasingly act in ill-disciplined, impulsive, illogical ways to create drama.

By contrast, the closest thing TNG had to a maverick was Riker (Jonathan Frakes), and the edgiest thing he did was grow a beard.

One hefty caveat: not all episodes were masterpieces. This was long before everything was serialised for the streamers’ binge model.

Back then, a duff episode didn’t mean you dropped out of the show forever, in the knowledge there were hundreds of other shows to watch, anytime, anywhere.

This was the 90s, so you just shrugged, faxed another Wagon Wheel to 2 Unlimited’s management, and hoped for a better effort next week.

You knew TNG could do things like The Inner Light [right], where Picard (Patrick Stewart) lives an entire life in an instant, a gift from an extinct culture that doesn’t want to be forgotten. Point me to a bit of TV with a grander imagination or generosity of spirit.

Because the biggest thing in TNG wasn’t the Borg Cube or the Gamma Quadrant, but its unlimited belief in human potential. This sounds daft, but when I think about TNG, the optimism it was powered by rises in me again.

But it’s bittersweet. TNG’s hope-stuffed stories of idealistic, rational heroes resolving dilemmas with restraint and intelligence feel like they belong to another time - and it isn’t, for the moment, the future.

- Sam Vincent is a writer and co-creator of Channel 4/AMC sci-fi drama Humans

Cult Classics

Mel Bezalel on Red Dwarf; Ross Bentley on Thunderbirds; Marnie Dickens on Buffy the Vampire Slayer; and other weird and wonderful favourites

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Sam Vincent on Star Trek: the Next Generation

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

No comments yet