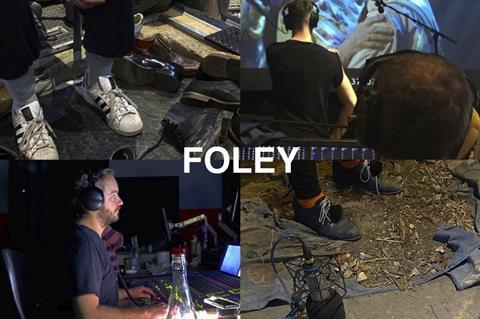

Broadcast drops in at Twickenham Film Studios to talk to the foley team about their fascinating work

Entering the large studio at Twickenham Film Studios where the mysterious art of foley takes place, the first thing that hits you, if you’ve successfully dodged all the car parts, shoes and random paraphernalia strewn over the floor, is the mess.

It’s as chaotic as a children’s nursery at the height of play – part of the floor is a muddy, sandy pit; there are big puddles of water elsewhere; rain jackets, various items of clothing, high-heeled shoes, bashed up boots, bits of metal, piles of different types of radiators, stones and rocks, sticks and who knows what else are all lying around nearby. I’m reliably informed these are all signs of a productive session.

I’m here to chat to the foley team behind No Time to Die, 1917 and a string of other big features over recent years. I meet foley mixer Adam Mendez, foley supervisor Hugo Adams and foley artist Sue Harding.

All were in the last week of working on Ron Howard’s Thirteen Lives, which seemed to involve a lot of water – the team explained that yesterday there was mess everywhere from all the water and mud being splashed around in the makeshift puddles of muddy water they’d created on the studio floor.

Harding began by explaining the role of the foley artist: “Foley is about creating sounds for the people on screen. First, you look at a scene and work out where the foley is needed. You then need to perform in a style that fits the action – that might mean wearing high heels, making powerful feet movements for a fight scene, or whatever. We have hundreds of different pairs of shoes in the foley room, and think about the combination of the shoe, the surface, the performance and what microphone is being used to create the overall effect.”

Picking up on the importance of the mic setup, Adams says: “We have lots of different mics here and know which ones are good for the type of sound we’re trying to achieve. During one walk, we’ll use a series of different mics and shoes, which we change between cuts. You need to believe in the movement, and that comes from the performance and the sound – the performance of the foley artist is incredibly important in making everything sound right.”

Mendez (pictured above) says: “We tend to capture footsteps with a boom, and the performer will move to precisely match the action on screen. Nothing in the foley can sound false, so all the random things need to be brought into the sound too.”

Most scenes in drama and feature films utilise foley to a lesser or greater degree. Typically, the foley team goes through every shot in a film and sets about using whatever equipment they think is appropriate to create sounds that make the human performance in each scene sound as authentic as possible.

The Twickenham Film Studios foley team started work on No Time To Die in the middle of 2019. Mendez explained: “We worked on the film in a piecemeal fashion, with two foley artists, two foley assistants, Hugo, me and an additional assistant in the studio. With Bond, there’s so much music and action, there are lots of big, loud scenes that require a lot of big sounds to be recorded into big sequences.”

Adams adds: “There’s a lot of foley in Bond. The opening sequence has a huge amount of feet in there. What we have to do is match the production sound and the foley, which is a very meticulous process. We’re recording sounds for whatever catches the eye. You’re using foley to pull the focus to whatever is on screen.”

To the untrained eye, it might be tempting to think the work of a foley artist is relatively straightforward – you just have to walk along, matching the footsteps on screen, or bash a few things to make them sound like things on screen – how difficult can that be?

Very difficult, it seems. As Harding explains: “To become good at foley is about time and practice. It takes five years to be confident you can deliver, and another 10 years to get to the level where you’re working on films like Bond. Props are like instruments, and we play them – we know the sound of each of the surfaces and what sounds we can get out of the different props in the different studios.”

Foley artists typically come from an acting or dance background, which lends itself to the performance aspect and flexibility of movement required for the role.

Perhaps surprisingly in the world of TV and film, the role doesn’t often extend to antisocial hours. Mendez says that Foley is a 9 to 6 job, where days are arranged around energy levels. He says: “It’s a very physical and very intense job that’s physically and mentally exhausting. So, you plan your day around that and do the bigger scenes when you have the energy.”

No comments yet