The show’s exec producers and US commissioner on taking a gamble live in primetime

There are around 14,400 seconds left of The Million Second Quiz and All3Media America chairman Stephen Lambert is gearing up for the grand finale when one lucky winner will receive a cool $2.6m (£1.6m) – the biggest prize in gameshow history.

It’s clear from the outset that this is no ordinary production. Billed as a David Blaine-meets-live-sport-meets-Big Brother event, and with a groundbreaking multimedia element on top, it is epic in scale and ambition; hence exec producer Lambert’s bleary eyes.

There have been nine stripped live primetime shows on NBC ahead of a two-hour finale, as well as round-the-clock filming as four contestants eat, sleep and play the trivia quiz, competing with each other as well as an audience playing at home via an app.

The set – a former Mercedes-Benz garage in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen – is vast and teeming with staff, some 500 at its peak. In the catering section alone, about 100 are tucking into a large buffet that includes duck and asparagus tips – a far cry from your usual chuck wagon.

Meanwhile, straddling the rooftop, and backed by an incredible 360- degree view of the Manhattan skyline, is a 50ft glass and steel structure forming the shape of an hourglass. It’s hugely impressive, but still that’s not all. The cherry on top is US media sensation and American Idol presenter Ryan Seacrest, rehearsing for the series’ climax.

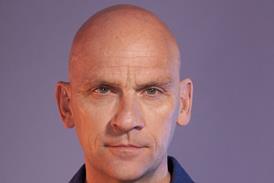

Lambert, who refuses to reveal how much sleep he’s had over the past 11 days, 13 hours, 46 minutes and 40 seconds, is nevertheless buzzing with excitement. It was just over a year ago that the idea was conceived by a UK development team at All3Media, and now here it is, at the heart of the NBC schedule, posing some 25,000 questions to viewers and contestants.

Going for gold

The show’s journey across the Atlantic was a relatively smooth one. Lambert was talking to UK broadcasters but also pitched the show to NBC’s president, alternative and late night programming,

Paul Telegdy, who, following the success of the Olympics, was looking for a big live-event show that could air for two weeks in the summer.

Even though there hasn’t been a live quiz show in US primetime since the long-running What’s My Line? left the air in 1967, Telegdy was keen – on the condition that it would air in the US first. He gave the team the resource to develop it just before Christmas and ordered a full series at the end of April.

“It was a big risk,” admits Lambert. “We never knew quite what it was going to be like. We didn’t know how long people would survive in the ‘money chair’ or how interesting the dynamics of ‘winners’ row’ would be, when the players started living with each other.”

The Studio Lambert chief exec says the broadcaster had the extra reassurance of knowing that Seacrest, another of the show’s exec producers and “the most talented on-screen host in America today”, would present it. NBC also got David Hurwitz (Fear Factor) on board as showrunner.

The show has a sizeable budget – somewhere between the cost of producing the Golden Globes and the Oscars, according to Telegdy – but ratings haven’t been quite as big. It opened with 6.5 million, dipped to a low of 3 million, but has climbed back to nudge 6 million.

Both indie and broadcaster acknowledge their disappointment with the numbers, but Telegdy insists it still represents value for money, estimating that over its run, it will get three times the reach of the Globes in the 18-49 demo.

The show has been heavily crosspromoted on other NBC shows, with key talent asking some of the questions from their own sets. NBC local affiliates produced packages based on those playing at home, and people with the highest scores were flown to Manhattan to compete on the live show.

“We’ve cross-promoted before, with talent sitting in the audience of other shows, but it’s never been integrated to this extent,” says Telegdy. “That sort of advertising would have cost us millions in airtime.”

Telegdy stands by the show in terms of its ambition to try something different.

He argues that anyone who isn’t willing to experiment in the face of increased competition for screen time “probably shouldn’t be doing their job”, noting the dip in TV viewing on the day Grand Theft Auto was released.

“It took $800m in sales on its first day,” he notes. “That’s what we’re competing against. TV is essentially ‘same meat, different gravy’; you’ve got to innovate to survive. You can’t be like Olivetti insisting that the answer to word processing is churning out more typewriters.”

The show has received mixed reactions, with some commentators suggesting the game is too complex – hence why the numbers were lower than anticipated.

Lambert admits: “It has been a huge learning curve. It’s delivered real drama every night and performed solidly, but we might simplify it and make some of the rules clearer.”

Telegdy says the show is likely to return to NBC “in some form” and he believes it has huge global potential.

Clearly, not everyone can recreate the stunning set and breathtaking scale of this series, but Telegdy argues that scale is not important: “The Manhattan backdrop was a luxury, but the essence of the show is an intense battle between two contestants, so you focus on their faces. This show could work anywhere.”

Lambert points out that when bad weather forced the production to move inside, it was a useful exercise in proving it could work well in a small, indoor setting – which would reduce costs significantly. “It’s highly adaptable,” he says of the show, which he is presenting to Mipcom. “We’ve had buyers here looking for different things and it’s clear we could make it work whether it’s a sports-themed quiz on a beach in Brazil, or a 90-minute German show focusing more on contestants’ back stories and the psychology of battle.”

Playalong app

One of the show’s biggest successes is the level of engagement with Monterosa’s playalong app, with Telegdy describing this meeting of online and broadcasting worlds as “a milestone”.

Launched weeks before the show, it has been downloaded by 2 million people, with 27 million game plays.

The app didn’t just market the TV property but generated a huge buzz by allowing people to battle head to head with a stranger between episodes.

Those with the highest scores could become ‘line jumpers’ with the chance to compete on live TV. Meanwhile, audio watermarking technology meant viewers at home could play along with contestants during the live show.

Most players were in the “impossible to reach” 18-34 demo, says Telegdy, and were massively engaged, even when the show wasn’t on air. NBC Universal digital distribution executive vice-president

Michael Bonner describes it as “well beyond anything we’ve ever seen before. It’s quite something. We’ve seen more and more people playing over the course of episodes; usually that’s flat or declines.” Sources suggest it has a response rate more than 10 times that of one leading talent show.

Its success means there is plenty of data to build on, both in audience engagement and sponsorship terms.

The show’s other executive producer, Eli Holzman, describes it as a “high watermark in digital engagement”. He adds: “We’ve fired a missile at the battleship; now we have to see what we’ve struck.

MSQ: Fact File

- Played 24/7 for 1 million seconds (nearly 12 days)

- Structured like a boxing event where a champion tries to hold the ring for as long as possible against all comers – in this case, via the Money Chair, where contestants notionally earn $10 per second

- Awarded biggest prize in gameshow history: $2.6m

- Stripped on NBC as 9 x 60-minute show at 8pm with 2 x 60-minute finale

- Game streamed on nbc. com for 23 hours a day

No comments yet