Fremantle’s president of global entertainment wants shows with mass appeal. It’s a belief that has brought us Got Talent and made the company into a major global player.

Fact File

Age 48

Lives Angel, London

CV May 2009-present: president, worldwide entertainment, Fremantle Media; 2004: joined Fremantle as senior vice-president of production of its worldwide entertainment department; 2002-04: head of entertainment, Princess Productions; 2001-02: head of entertainment, SMV, also overseeing Ginger productions; 1995-2003: co-creator and co-writer, ITV sitcom Barbara

Watches Britain’s Got Talent, history-based Discovery programmes. “Pharaohs, ancient Egypt. Anything to do with medieval Britain.”

Dislikes “Big Brother. I just hate it. I adore Davina, she’s a good friend, but I can’t stand it and I used to be a big fan.”

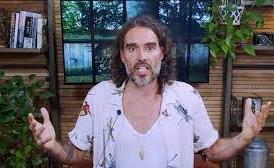

When he joined Fremantle Media in 2003, Rob Clark was charged with growing an outdated portfolio of classic gameshows such as The Price Is Right and the Idol franchise to make the company a leader in global entertainment.

Clark has revolutionised the company’s catalogue through acquisitions, partnerships and in-house brand development, and was recently promoted to president of Fremantle Media’s global entertainment division.

He now oversees the distribution of shows such as The X Factor, Britain’s Got Talent, Hole In The Wall, The Apprentice and Farmer Wants A Wife to broadcasters across the world.

Broadcast caught up with the entertainment producer on the eve of Mipcom to find out how he plans to help steer the global giant through the economic gloom by maximising the company’s brands, negotiating budget cuts and acquiring more factual entertainment.

What changes are you seeing in the market?

There is a revolution in which platforms you can broadcast your content on - and it has changed every territory beyond belief. It affects your production team and how big it is. And budgets are a lot smaller now.

In the old days, you would be able to acquire a format such as The Apprentice once it had gone on air. Now those days are over. A programme of that magnitude would not get on air now without having some sort of worldwide deal already in place. My team and I have to make decisions at a very early stage now - often on paper - about whether a format has potential to have global reach. That makes it a lot harder than it was because you can’t just say “acquire that, it’s the number one show in America”.

How have smaller budgets affected your team?

Young producers will need to face up to the fact that the number of platforms on which they will have to put their programmes will increase, but the amount of money they have to do that will be reduced. They need to learn very quickly how to make those programmes for less money, but still make them as engaging.

Broadcasters also want to reduce the risk of a programme failing. One sure way of doing that is to make sure that you’re buying things that have worked well elsewhere.

What else can you do to reduce that risk?

One of the things we look at is whether we can make a format global. I think we’ve done that more than anybody else. If you look at Got Talent or Hole In The Wall in Indonesia, India, America or in the UK, they actually look alike. They have cultural appropriateness but there’s a brand to them.

Programmes don’t survive any longer by having a one-hour-per-week window on television. They have to have websites, they have to have more information, they have to be available to be replayed on iPlayer and all that sort of thing. If you don’t listen to your audience, or look at trends, then you will suffer. You need to be able to respond quickly.

What has been the impact of budget cuts on your business with regards to funding models?

The broadcast landscape has shifted a lot. Whether we ever go down the fully funded route again for mainstream primetime entertainment - I don’t think that’s feasible. It’s too expensive. I suspect there will have to be a rejigging of production models around the world in virtually every territory.

From a co-pro point of view, we have a history of co-producing with a lot of our main format owners. That is something we will definitely continue doing because I think it brings two different perspectives to the same party. From a production point of view, there are benefits, mainly in the way you can look at different production models, and making things not necessarily more cheaply, but more effectively.

How are your programmes performing internationally?

Programmes such as The X Factor and Idol have had a good year, Got Talent has had a phenomenal year and all those big traditional family shows have performed incredibly well. The Price Is Right is back on air after a period of 20 years in France, and it’s a top 10 show. Family Feud is back in more than 20 territories and Let’s Make A Deal has just come back to the US after 20 years. They have been re-versioned slightly so they don’t look like museum pieces.

Why are they selling well now?

Entertainment formats often do better in recessionary periods because people want a bit of comfort when they go home.

What are the gaps in your slate?

On the whole we’ve got a pretty balanced slate. We’ve got field reality, cross-genre reality shiny floor, shiny floor Saturday night, gameshows, comedy, and comedy gameshows. So we’re well balanced in terms of access prime and primetime, which has been our main focus. If we were looking, it would be for more factual entertainment, field reality and gameshows. Gameshows will always be on the board, because you can make five a day and they can be fantastic ways of utilising the economies of scale between a company such as Fremantle or even within a production company. In terms of the big shiny floors, we’re pretty sorted.

I do think we are going to see a growth in factual entertainment. We had that golden period with shows such as Wife Swap and Faking It, and we had How Clean Is Your House? in the late ’90s. I think we will be looking to find, either through creating them ourselves or through acquisition, some formats in that area now as well.

Would you ever look at replicating Endemol’s Total Wipeout production model [ie, one global location]?

If you can think of any production model, the Fremantle team somewhere in the world will be ‘sucking and seeing’ [whether it works] over the next year.

What is your advice to indies about getting their formats in front of Fremantle?

In the UK, if you have a commission, come in early. It doesn’t have to be on air. Talk to us. Or if you want to come in and talk about a different sort of relationship, a longer-term relationship, that’s great. The face of the industry is changing so quickly that virtually anything is feasible, and one of the things I like about Fremantle is that, for a big company, we can spin on a sixpence.

We have many different ways of working with partners. Once that dialogue is open, it comes down to two things. One is the format and whether we like it, but, if it’s a longer-term relationship, we also think about whether we are going to get on as companies and believe that a business partnership can grow. That is really important.

What needs to change for the industry to thrive?

The fact that most people in television are middle-class, live in Wimbledon and have parents who have worked in television is, I think, disgusting and has a grave impact on how programmes are made.

I worry that [entry-level positions] don’t pay much, so on the whole you see people who live with their parents, or have parents who can support them. You’re talking about a bunch of middle-class white kids who have to live locally. That is not a good thing.

When I was a kid I liked to see people like me - teenagers and Northerners - on television. That’s really important for everyone. We represent a multicultural, multi-racial society very well on shows such as Britain’s Got Talent and The X Factor. That’s what I call New Britain and it’s not done for a political dictate, but because it makes better television.

What lessons have you learned from having a worldwide focus?

We shouldn’t chase speed. I always think we should chase quality of roll-out, and sometimes it’s much better to have a slow approach that works rather than a very quick pace of sales all over the world, because it makes it very difficult to learn from one territory to the next.

People all over the world are pretty similar - they laugh at the same things, they cry over the same things. At the end of the day, entertainment is about laughing and crying - which is what I do almost every episode of Got Talent.

Healthcheck

Top selling formats

- Idol 43 territories

- Got Talent 34 territories

- Hole In The Wall 42 territories

- The Apprentice 15 territories

- The X Factor 18 territories

- Let’s Dance Four territories

Weak spots

Could use more field-based reality and factual entertainment shows like The Apprentice that will translate well around the world, to sit alongside is glossy studio formats like Got Talent. Older shows such as Idol and X Factor also need constant reinvigoration.

No comments yet