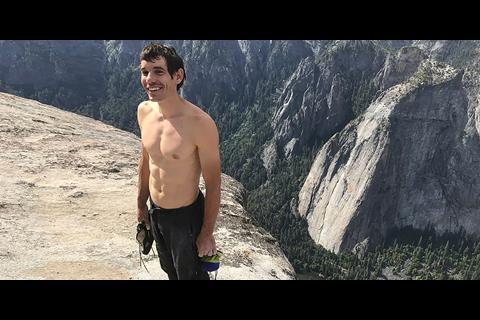

How the presence of a film crew actually helped free solo climber Alex Honnold scale the 3,000ft El Capitan

When husband-and-wife film-makers Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi decided to make rock climber Alex Honnold the subject of their next documentary Free Solo, they didn’t anticipate they would be embarking on a two-year-plus odyssey that would culminate in a death-defying ascent of the El Capitan rock face in Yosemite National Park, California. The plan had been to make a character study of their friend who was renowned for free soloing — climbing with no ropes, using only hands and feet.

It was only once they started filming that Honnold informed them of his intention to focus on his long-cherished dream of soloing El Capitan — a near 3,000ft-high rock formation with an almost vertical face. It was a task many thought impossible, with death a very possible outcome.

“It wasn’t as if I suddenly decided,” insists Honnold. “I agreed to the project knowing the only thing I cared about was free soloing El Cap. It’s just they didn’t know anything about it.”

Chin and Vasarhelyi immediately paused the project as they wrestled with the ethical implications of Honnold’s decision. “I was already uncomfortable filming him free soloing, even without El Cap,” says Chin. “You don’t want to be the one that’s pushed him to go do something and he falls.”

After six months of soul-searching, they decided to keep going. “We believed in Alex and trusted his decision-making,” Chin continues. “We assumed he was either going to do it or practise and realise he couldn’t. He was never going to go for it if he wasn’t 100% prepared.”

As the film reveals, Honnold is nothing if not prepared, and he says having a camera crew follow him around during the entire process actually helped curb his more impulsive tendencies. “You can’t just wake up and go,” he says. “You have to tell them what you’re doing so they can film it. Which definitely makes things safer. When your friends are there, watching, you do your best to make sure you don’t embarrass yourself in front of them.” Or die. “Exactly. That would be the ultimate embarrassment.”

Navigating multiple hurdles

Chin and Vasarhelyi’s documentary is a beautifully shot portrait of a remarkable human being working out how to overcome seemingly insurmountable odds. It is also the moving story of Honnold himself — a shy, awkward loner who, the film hints, was starved of intimacy as a child and began free soloing because it was easier than interacting with other people. “That gave it emotional depth, because it wasn’t just about courage, it was an emotional fear he had to overcome,” says Chin.

During filming, Honnold began dating Sanni McCandless, a young woman he met at a book signing. “When she first came in, we were really worried,” admits Chin. “We didn’t know how serious they were going to be, and we were worried she might distract him from his goal.” As it turned out, McCandless proved to be a godsend to both Honnold and the film. “Because this is much more interesting than Alex sitting in a van by himself,” reflects Chin. “He has no language for talking about emotions, relationships. And here’s this woman who is totally articulate about the emotional landscape, and helps give him a language to connect. In some ways, the relationship is the other mountain he needs to navigate.”

In the end, the filmmakers shot more than 700 hours of footage, with Chin in charge of the mountain and Vasarhelyi documenting the drama on the ground. When it came time to record the actual ascent, the crew had spent as much time on El Capitan practising as Honnold. “We choreographed where we wanted to be, which sections were important to the narrative,” says Chin. “It was a 3,000ft wall, so we couldn’t cover it all, although our long lens on the ground covered the entire climb. And we had a helicopter flying at 3,000ft [above the summit] with a 1,000mm lens.” Chin himself was dangling on a rope at Enduro Corner, 2,400 ft up — one of five camera operators on the face, along with multiple remote-triggered cameras. Another six camera operators were at the base.

Free Solo has earned US$13.1m at the US box office since National Geographic Documentary Films released it last September. It is UK outfit Dogwoof’s most successful documentary release ever, taking more than US$1.7m (£1.3m) since its December 14 opening. Chin believes his film’s success, alongside other recent documentaries such as Three Identical Strangers, RBG and They Shall Not Grow Old, can be partly attributed to audience access to streaming services. “I certainly think Netflix has had an effect, in that it’s trained people to appreciate non-fiction as a form of entertainment, as a form of truth,” he says. “It’s reached a tipping point where everybody’s embraced non-fiction as a legitimate form of entertainment.”

For daily broadcast sports stories, covering sport production, distribution and tech innovation, visit Broadcast Sport and bookmark the Broadcast Sport homepage, http://www.broadcastnow.co.uk/sport

While Free Solo has been nominated for a Bafta and an Oscar, for Chin its success is measured differently. “Success, for this, was Alex surviving and the whole crew staying safe,” he says. “I think people are connecting with this idea of radical, intentional living. Here’s this guy who’s thought about his mortality more than most, and he’s so true to himself. It’s also about courage — facing your fears. He’s doing it in a way that seems inaccessible, but the way he approaches it is accessible. You can achieve the impossible through dedication and hard work.”

This article was first published in Broadcast Sport’s sister publication Screen International. It was written by Mark Salisbury.

No comments yet