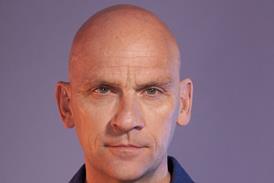

Following the sudden death of the RDF Media founder, friends and colleagues reminisce about the man who championed producers and helped grow the indie sector

If you could bottle the essence of an ideal indie boss, it would likely contain the best qualities of David Frank. A producers’ champion and shrewd negotiator who rolled the dice on both leftfield business deals and risky creative ideas, the RDF Media founder is credited with helping the indie sector grow up without losing its sense of fun.

Hundreds of friends, colleagues and contacts reached out to the Frank family following the news of his sudden death last month, aged 63. Frank was an informal mentor to many, and influential in kick-starting many careers – and not just in the distant past: current BBC commissioners Jack Bootle and Abigail Priddle had lengthy early spells at RDF.

In a move almost as legendary as RDF’s Mipcom yacht parties in Cannes, Frank put up his house as collateral to found RDF in 1993. The former investment banker and business journalist quickly deduced that there was no reason why an indie should limit its ambitions, even though, as his brother and business partner Matthew attests, the company nearly went bust in its hand-to-mouth early days.

The Franks were close to throwing in the towel when they landed a last-minute £180,000 commission for Channel 4’s High Interest strand in the mid ’90s, after another indie’s idea fell through.

Cathy Rogers, who joined RDF in 1995 and later headed its US operations, says Frank’s infectious appetite for experimenting was immediately evident.

“His approach was, ‘we’re smart, we can fill in the gaps where we don’t have the knowledge’,” she recalls. “He had a fantastic sense of can-do and genuinely loved taking risks. This has become a cliché in describing entrepreneurs – a lot of them actually don’t – but he was prepared to put everything on the line if he had an instinct about something. He never really lost that.”

“David was wonderfully open to new ideas… He never felt there was a limitation on what we could do”

Nigel Pickard, Long-term colleague at RDF, Zodiak and TRX

Nigel Pickard, who met Frank a decade later and came aboard as director of kid’s, family entertainment and drama, remembers a man hungry to learn about different genres. “David was wonderfully open to new ideas. He grasped things really fast and never felt there was a limitation on what we could do.”

This extended to indies as a whole – Frank was one of the main drivers in uniting broadcasters and MPs to secure the landmark industry Terms of Trade in 2004.

Pact chief executive John McVay says Frank attended every possible meeting and scrutinised every line to find ways to exploit ambiguous wordings and gaps to indies’ advantage – and in one memorable moment, responding to a better-than-expected BBC offer with a poker face, leaving the room to cheer with his peers before returning with a solemn acceptance.

All3Media chief operating officer Sara Geater, who was sitting on the other side of the table at C4 at the time, remembers fondly the “wealth of experience and sense of humour” that Frank brought to often “fraught negotiations”.

McVay adds: “David did all this with good grace and charm and if you were working with him, he was ‘in the room’ the whole time. Until then, the industry was chock-full of smart people but didn’t really have a full business model.”

Frank’s vision for the industry impressed Stephen Lambert, who was RDF creative director at the time. “Until then, indies were serfs working for broadcasters. David was brilliant at getting the message through that dispersing capital would make for a more creative indie sector, as companies would have the resources to back their hunches and retain talent.”

Bringing Lambert into the fold in 1998 was one of Frank’s biggest swings. This would usher in RDF’s purple patch of Faking It and Wife Swap, but at the time, it was seen as a major gear shift.

Heading out in his Mini to woo Lambert over lunch, Frank told Rogers that RDF was a lower-league football club trying to sign David Beckham, such was the improbability of success. Business was worryingly quiet during Lambert’s first nine months, but the pairing soon clicked and RDF truly took off under its most successful creative exec.

For Rogers, “this was a brilliant example of David not thinking one step ahead, but 10 – ‘what’s a clever move now to get where we want to get to more quickly?’”

If Frank saw something in someone, he would give them a chance, and many former colleagues remark on how his faith in them was transformative.

After Julia Waring’s first job for RDF in 1997, Frank sent all staff a handwritten card and a bottle of champagne. She thought: “I want to work with this man” – and she did, for 24 years until August this year. The label’s long-term head of talent helped to shape a company culture that was informed by the Frank brothers’ fabled ‘no wankers’ ethos.

“David was full of fun and reassurance – you wouldn’t like to disappoint him”

Julia Waring, Former head of talent at RDF Media

Waring contrasts Frank’s willingness to take risks on new talent with the industry’s more conservative approach today. RDF was energetic and creative, fuelled by hard work. “David was full of fun and reassurance – you wouldn’t like to disappoint him,” she recalls.

“He encouraged people to get things done and we followed his lead. He loved hard work, but he created such a warm environment, with Thursday drinks and summer or Christmas parties. He was a very approachable managing director.”

Waring’s own approach mirrored that of her close friend. “I looked for authentic people who wouldn’t stab their granny in the back. I’d take somebody with the right personality over a person who was super smart but incredibly ambitious. Every employee represented RDF, and we made people-based programmes. The public didn’t want us to be intimidating or pretentious, or conform to their idea of what a media person was.”

Pickard says Frank was the best boss he ever had, but he was no pushover. “David was very visible and accessible, but he would quiz you. If you needed budget for recruitment or development, he’d always get you to articulate it so he could support you. You had to prove your point.”

Beneath an inspiring and extrovert exterior, Rogers says, Frank had hidden skills that were worn lightly and deployed to make others feel they had his total attention whatever the situation. Those attributes came to the fore when the scale of his job leaped under Zodiak’s ownership of RDF from 2010, when Frank became chief executive of the wider group.

“There’s a lot of machinery when you’re running a group of that size, but he still found pockets of glitter within it and still loved trying out new things,” says Rogers. “He didn’t see the point of faffing around – if you can cut some processes out, why not do so? This is such an unusual and special approach that brings out the best in creative people.”

David’s optimism saw the company through its more challenging times, such as the ‘Queengate’ affair that led to Lambert’s departure in 2007. “I’ll remember David’s smile and his laughter,” says Lambert. “He always had something new to show you and a great passion for what he was doing. That was never earnest but mixed with a great and infectious sense of fun.”

The Frank brothers left Zodiak in 2014 and their subsequent distribution ventures The RightsXchange (TRX) and Dial Square 86 reflect David’s eye for innovation and ability to spot a gap in the market, says Pickard. “He valued content and how you exploit it, and knew the importance of having control of IP within your arsenal. His enthusiasm was not diminished by those Zodiak years. He was excited to have a new way of looking at things.”

Underpinning it all was the tight-knit relationship of the two brothers, forged in boarding school and maintained through their shared love of Arsenal, fly fishing and golf. “Going into business together one day always seemed like the natural thing to do,” says Matthew. “We always consulted each other, but David made the final decision if we disagreed on something. He was my older brother, my best friend and my business partner – that’s very special.”

That passion will leave its mark on generations of producers. “David did a huge amount to help the indie sector be seen as grown-up – not a lifestyle operation but a serious business that should be respected,” says Rogers. “And somehow, he did that with a twinkle in his eye and a skip in his stride.”

Geater agrees. “David was fun, clever and wise. The world is going to be a more boring place without him.”

1 Readers' comment