Going right into the eye of some of the world’s worst hurricanes was the most dangerous and ambitious idea I’d heard for a TV show – I was immediately sold, says Caroline Menzies

Production company ScreenDog Productions

Length 8 x 60 minutes

TX 7pm, Sunday 24 March, Dave

Commissioner Helen Nightingale, UKTV

Co-series director / producers Oli Sloane; Caroline Menzies

Producer/director James Levelle

Presenter Josh Morgerman

Executive producer Ed Kellie

Assistant producer Catriona Wright

So you’re a bit like Helen Hunt in Twister?”

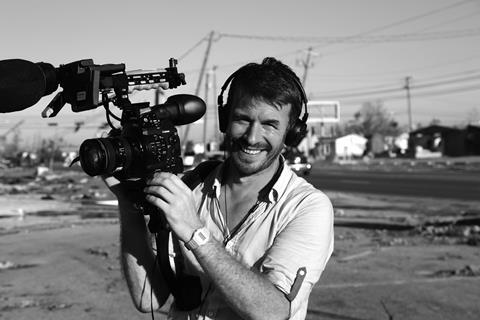

That’s what people generally ask when I tell them about my role on Hurricane Man, a documentary series-meets- disaster movie for UKTV in which I and two other directors (Oli Sloane and James Levelle) follow the world’s top hurricane chaser, Josh Morgerman, collecting meteorological data from 2018’s worst storms.

We also filmed first-responders and families that refused to evacuate. I remember meeting executive producer Ed Kellie for a coffee in Soho to discuss the project.

I gulped down my latte in one as he cheerfully explained his mad idea of sending a documentary team into the eye of the world’s most violent cyclones. It sounded like the most ambitious, adventurous and dangerous idea for a television series I’d ever heard of. I was sold.

Hurricanes come with inherent dangers – storm surges, flying debris, violent winds and so on – so the biggest challenge for joint series producer/director Oli and I was working out how to make the series and not die in the process.

We are all experienced adventure film-makers – between us, we have filmed in remote Siberia, lived off-grid and worked in some of the world’s most hostile environments. But hurricanes come with a unique set of challenges: 145mph winds mean you can hardly stand up (let alone wield a camera), and rain at that speed feels like shards of glass hitting your skin.

Hurricane wind sounds like a highspeed train, so recording sound is a nightmare and, crucially, filming an incoming natural disaster means you are entering mandatory evacuation zones where even first-responders will no longer be able to help you at the peak of the storm.

We did a bespoke training course devised by Remote Trauma, in careful consultation with our hurricane expert/presenter Josh. This involved crawling through collapsed buildings, climbing over unstable debris with camera equipment, learning to interpret storm radar and satellite imagery and recognising the difference between a Category 1 and a Category 5 hurricane.

Pre-planning and budgeting were not easy because hurricanes are so unpredictable. They hit the northern hemisphere from July to November but give little warning, so we had just a few days to decide on whether a hurricane was worth chasing, fly across the world before it hit, get to ground zero before landfall and quickly find local families on the ground to film with.

Caroline Menzies - My tricks of the trade

-

Cheap ‘hacks’ can be used to storm-proof kit. Polythene and gaffer tape work as well as expensive rain covers. Try putting mic packs in condoms with an elastic band around the top.

- There are some great apps, like Storm Radar, that help to keep you alive.

- While you should secure a lot of access in advance, on-the-ground enquiries can lead to the best stories.

- On social media, search relevant hashtags to find local families staying behind.

- Never try to fly a drone in the eye of a hurricane – you will (nearly) always crash it.

We spent two months gaining difficult access to governments, disaster emergency agencies, armed forces, NGOs and first-responders, many of whom we never actually needed to film with – much to their relief.

Our office walls were plastered with maps of hurricane-prone locations, including the Caribbean, the Gulf Coast and the east coast of the US, Taiwan, Japan, Mexico, the Philippines, Bangladesh, India and Oman.

We couldn’t possibly afford visas, filming permits and fixers to set up access to all these locations so we had to make informed guesses as to which countries and regions were most likely to be hit by a hurricane and be on constant standby.

Finally, after an unnervingly quiet start to the hurricane season, we got our first ‘chasable subject’ – a double whammy as two typhoons (the name for hurricanes in Asia) were due to strike Japan within 48 hours of each other.

The stakes became even higher – our presenter and executive producer wanted us to get inside the violent eye-wall of both storms, even though they were hitting hundreds of miles apart at a time when flights would be grounded, and roads closed because of the risk of landslides.

Remarkably, we managed to chase down and film a total of nine major cyclones across the world – in Japan, Mexico, the Philippines and the US – including Hurricane Michael, the fourth-worst hurricane to ever hit the US, which tragically killed 45 people.

We embedded in family homes, fire stations and community shelters. We got intimate access to first-responders who let us join them in boats, helicopters and trucks as they rescued victims.

Despite filming some harrowing scenes and being caught up in terrifying near-death situations, among the devastation we found stories of hope, resilience and community spirit that renewed our faith in humanity.

One contributor told us: “It’s sad that it takes a hurricane to make you realise what’s really important in life.” That thought has really stayed with me.

CAPTURING THE AFTERMATH

Oli Sloane - Co-series producer/director

Much of the problem wasn’t filming during the hurricane, but filming after it.

The first thing to go during a hurricane is electricity – this almost always happens. With no power, the pumping stations don’t work, so water disappears too. Fuel is also in finite supply. The city is plunged into darkness, running out of water and literally grinding to a halt.

Three days after a substantial natural disaster, peaceful society starts to break down. We often saw people fighting over resources. It felt much like we were existing in a post-apocalyptic computer game. Money meant nothing – food, water and fuel were everything.

The survival experts told us to hide a second stash of resources in case we were car-jacked, but we kept everything hidden – our main stash and back-up. Ironically, this didn’t apply to our camera equipment. We could leave that on the back seat of a car with four smashed windows – it wouldn’t help people survive. But we had to make a TV programme too.

We would carry enough batteries for two days’ filming and charge these up using a DC inverter in the car. It is surprising how much fuel it takes to charge a camera battery. We had to calculate how many miles we would need to drive for the next day’s shooting and how much fuel it would take to charge our kit.

Much like a computer game, inventory was everything. We could use our resources either for their intended purposes or to barter.

One time, we were filming in a demolished hotel and found an unopened pack of babywipes. This was like gold-dust in a city whose people hadn’t washed for four days.

In the end, we gave them as a gift to one of our closest contributors, but some resourceful guys selling jerry cans of fuel by the side of the road said they would have preferred them over the cash, beer and protein bars we actually paid them with.

No comments yet