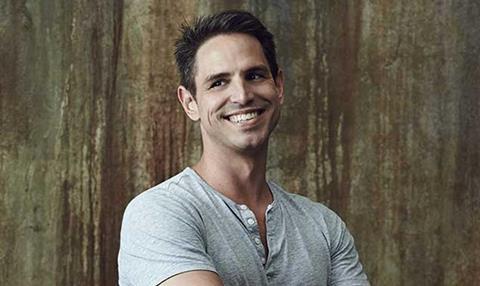

The Tomorrow People and Arrow showrunner discusses genre-hopping

Fact File

Age 41

Lives Los Angeles

Company Berlanti Productions

First-look contract Warner Bros

Career

Selected TV credits

2013-present Executive producer, The Tomorrow People (The CW)

2012-present Executive producer, Arrow (The CW)

2012 Creator, Political Animals (USA Network)

2008-2009 Executive producer, Eli Stone (ABC)

2007 Executive producer, Dirty Sexy Money

2006-2008 Executive producer, Brothers & Sisters (ABC) 2002-2006 Creator/ showrunner, Everwood (The WB)

1998-99 Writer/ showrunner, Dawson’s Creek (The CW)

Selected film credits

2014 Producer, Pan

2011 Writer, The Green Lantern

2010 Director, Life As We Know It

Greg Berlanti is living a geek’s dream. Having revived The Green Lantern for the big screen, the New York-born writer and producer has two major fantasy franchises on air back to back on The CW Network: a reboot of cult UK show The Tomorrow People and DC Comics adaptation Arrow.

But it wasn’t always this way. Learning his trade on Dawson’s Creek, he was initially perceived as “that teen guy” before breakout hit Everwood and then Brothers & Sisters made him synonymous with family drama.

Moving on and switching genre just as he risks becoming pigeon-holed suggests an enviable sense of self preservation in an industry in which you’re ultimately only as hot as your last hit. But fantasy is a law unto itself, with hungry, opinionated fans to satisfy or enrage, back stories to honour and series-long arcs to plot. Does he know what he’s let himself in for?

“When I started on Dawson’s, we’d get a box of fan letters once a month,” he recalls with a laugh. “Now they’re tweeting live while it’s broadcast. You have to be immune to some of that but you can make changes quicker, if you’re flexible and prepared, by gauging what you think is working.”

On Arrow, Berlanti and co-creators Andrew Kreisberg and Marc Guggenheim start by pleasing their inner fanboys. “The studio will ask ‘how will the fans feel if this happens?’ and we’ll say ‘we are the fans’. You can’t be too landlocked into things.”

He does, he admits, wear this label lighter than some of his peers. He remembers escaping into comic books in his early teens but “I had other things already challenging my dating life”. Yet this was the golden age of Marvel and

DC Comics and it couldn’t help but leave an impression. “It’s no surprise to me that the kids who read the stories of that era have grown up to tell these stories for TV and the movies.”

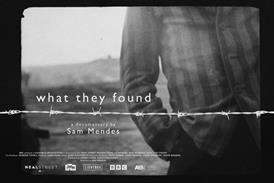

The Tomorrow People, the 1970s Thames TV series about telepathic teens, seems an unlikely candidate for a US makeover, particularly with the similarly themed X Men franchise eclipsing it in the public imagination in the interim. But Berlanti spent a decade hunting down the rights to revive a show that had obsessed him as a child.

Cult follower

“Nickelodeon would run them in a stretch every day as a serial,” he recalls. “With VCRs only just starting to happen, I devoured it as a true cult show. There was a part of me that wasn’t even sure that I remembered it properly.”

Meeting fellow fan Julie Plec at college – she’s now an executive producer of the show – proved a catalyst to the protracted process of acquiring the rights. So what captured his imagination about the show?

“That feeling of not being weird just because you’re an outsider. It’s an empowering story and the one thing we wanted to capture from the original was that sense of escapism.”

Nerves about the show’s reception in the UK dissipated when it landed with 1.4 million, a record debut for a US acquisition on E4, with subsequent episodes averaging above 1 million (including narrative repeats). From summer blockbuster sequels to ABC’s Marvel’s Agents Of S.H.I.E.L.D., audiences are hardly starved of superhero stories these days and Berlanti’s feeding this hunger with The Flash, a spin-off from Arrow.

Having written for both the big and small screens, he’s keen to maintain the distinction between the “big, high octane storytelling” of the cinema and the more novelistic approach of TV, where “you can build the universe and go off in this corner in one episode and twist it round for the next one”.

After Lost stretched audiences’ tolerance for multi-season story arcs to breaking point, spawning pale imitations with premises exhausted soon after the pilot, high-concept stories fell briefly out of favour with US network execs. But this, like so much else in TV, is cyclical.

“I’ve been told at least three times in the past 10 years of pitching that no one wants serialised storytelling and it’s always proved untrue,” Berlanti says. “Now we’re being asked: ‘Are there other ways you can make it more serialised?’ You have to decipher what each show wants to be, and not turn it into something it’s inherently not.”

For example, Green Arrow, the comic on which the series Arrow is based, has a five-year origin story for the main character, providing a neat fi t with the syndication sweet spot of 100 episodes – fi ve years of US TV. This anchors the show with a solid base, around which more stories of the week and other tangents can be kept spinning.

The trick, he says, is to keep a healthy mix of writing staff. Not every comic book writer can translate their skills to TV, and shows like these need to honour the core fans while reaching out to more casual viewers. “The biggest success for me is if my mum or sister watches it – and not just because they’re related to me,” Berlanti says.

Any writer will tell you that a drama ultimately lives or dies by its characters, and this is what transcends genre for Berlanti. While he awaits a decision on The Tomorrow People series two, he’s developing a pilot for NBC modelled on Spanish series Mysteries Of Laura – “a female cop show in the vein of Columbo” – and wants to write a more personal piece in the mould of USA Network’s 2012 series Political Animals, his sole cable show to date.

Showrunner limit

He sees two or so years as the right innings for a showrunner. “You don’t want to be someone who hangs around offering their views on a show. I think about it like a fan – I didn’t think anyone could replace Aaron Sorkin on The West Wing, but those last two years under John Wells were as enjoyable as anything on TV.”

He takes his showrunning duties seriously – “I’m there from genesis to execution. My name’s at the front and end of the show and I’m responsible no matter how much I write” – but says there’s no point being precious about taking credit in a collaborative medium.

And he has little time for the playing- to-the-crowd “down with notes” rallying cry of Kevin Spacey’s MacTaggart speech.

“Network executives are your first audience and if you stop looking at them as people in suits trying to destroy your baby, you see they’re actually trying to help you,” he says.

“If something’s not working, you’re going to hear it eventually, from actors or others. My mum will call me if she doesn’t like something. There have been times I’ve won the battle over notes and then watched as the audience has the same reaction as the executives. I’ve had to take a step back and become more open-minded.”

It’s a game, in other words, in which the writer’s voice is but one of those worth listening to. Berlanti learned this the hard way in his formative years in TV. Kevin Williamson picked him as a staff writer on series two of Dawson’s Creek after the pair had worked together on a film. Williamson then moved on, taking a couple of writers with him. Returning for series three, Berlanti was presented with two show- runners above him and several new writers. One by one, they all left.

“It was like Ten Little Indians,” he laughs. “Then, because I’d written on maybe 10 of the 20 or so scripts of season two, Warner Bros asked me to step up and showrun. I politely declined, thinking ‘well, that’s a poisoned chalice’. But they intimated that it wasn’t really a choice.

“I did that for a couple of years and learned a lot, but much of it was happy accident. From then on, I’ve been running writers’ rooms and doing the other side of the job as producer.” He leans back and grins. “So the moral of the story is: don’t get fi red.”

Greg Berlanti on….

New voices

“Every year I try to produce a pilot for someone else; it’s invigorating. And I try to bring in a lot of new voices each year because I came up that way. There’s a chain of command, but anyone can write a scene.”

US networks

“They’re trying to redefine themselves and make their shows events in the cable era. The question is whether procedurals can still work and be loud enough to get people talking. That’s why you see that drift towards pre-existing formats, big names or iconic ideas, whether supernatural or storybook characters. Whatever audiences can latch onto.”

British TV

“I loved Being Human and No Heroics [the ITV2 superheroes sitcom from a few years back]. But the show that’s moved me the most in the past year, from anywhere, is Broadchurch. The intimacy of it was so powerful.”

No comments yet