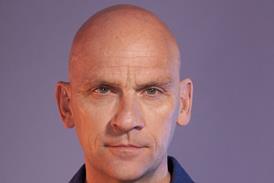

2012 has been a prolific year for Gordon Ramsay and his indie One Potato Two Potato following a series of hit US shows for Fox. But he won’t forget his roots, he tells Chris Curtis

It’s hard to believe, but Gordon Ramsay loves Mipcom.

Aged 24, the Michelin-starred chef was gaining experience working for Alain Ducasse in Monaco when a customer offered him a job as a private chef on a yacht. That customer was Reg Grundy, who employed Ramsay for a year, including a big event at Mip. At the market, the Australian media mogul asked Ramsay whether he did much TV? “You’re kidding,” he replied. “I don’t do TV, I’m a real chef.”

Twenty years on, Ramsay and Grundy are still friends - but the Scottish chef does more than his fair share of TV. Much of his output is with One Potato Two Potato (OPTP), the joint-venture production company he set up with long-term partner, and All3Media stablemate, Optomen Television.

2012 has been another prolific year on Channel 4 for Ramsay, with Gordon Behind Bars, Gordon’s Ultimate Cookery Course, and, right now, Hotel GB. But it is in the US where this year has been genuinely transformative, with Ramsay and Optomen’s Ben Adler and Pat Llewellyn collectively producing 85 hours of OPTP programming for Fox.

Their most recent show, Hotel Hell, is also their most significant: while the other Fox series are co-productions - MasterChef US is made with Reveille, and Kitchen Nightmares with Arthur Smith & Co - Hotel Hell is purely the work of OPTP. They see it as a breakthrough - Adler describes it as “having our hands completely on the train set” - and it was Fox’s top-rating show of the summer. Hotel Hell is not a radical departure from the business makeover genre of Kitchen Nightmares, but there is a difference in feel and tone.

Ramsay says: “We tried to make it more of an ob-doc, akin to the first few series of Nightmares in the UK. In the US, Nightmares is bold and brash, but in Hotel Hell, we wanted to bring out the seriousness of the business. The team was smaller, the budget tighter, but we delivered a programme with greater integrity.

“Ben came up the idea of bringing all the customers into one room for a confrontation, and I was almost void -

I said almost nothing. We had intimacy, there weren’t eight or nine cameras or robos everywhere, it felt like a documentary.”

Hotel Hell was ordered by Fox’s eccentric president of alternative entertainment Mike Darnell, who, according to Adler, “sings songs and gives you tequila shots in meetings, but is laser sharp across everything”.

Llewellyn admits they were a bit nervous and “hid behind Gordon as we threw him into the office” during the pitch. “The US isn’t as keen on taking risks as we are, so we knew Hotel Hell should build on the strengths we have of business makeovers. We were a bit more playful with it, and Gordon is a bit softer,” she says.

Growing beyond Gordon

OPTP’s US expansion is now a key priority and Ramsay has many other projects on the boil. He reveals an unusual push into drama with two developments in the works, and the chef is on the verge of discussing other projects when a slightly flustered Adler encourages him to shut up.

But Ramsay can’t hide his pleasure at winning orders or resist a little dig back. “I look at it as Michelin stars when we get commissioned,” he says. “Pat looks at it in terms of Baftas and Ben looks at it as profit. That’s how we work.”

One pilot is Food Court Wars for Food Network in the US. Ramsay is clearly attracted by the vast footfall of US shopping centres, and the competitive format pits two teams against each other, cooking locally inspired food to win a rent-free restaurant space. It was filmed in the summer and is hosted by chef Tyler Florence, who is among the station’s key talent.

It’s signifi cant that Ramsay isn’t on screen, which is part of a strategy to allow OPTP to grow beyond shows that place a significant demand on his time. He is an executive producer of Food Court Wars, as he was on My Kitchen - a 40 x 30-minute commission for UKTV’s Good Food - but they’re not vanity credits, he says.

“I know my pitfalls and strengths. I’m not a genius in edits, but I can nurse talent and give them confidence. It’s about giving the insights on how to deliver on screen rather than worrying about the Good Food Guide.”Instead, he’s helped the likes of Angela Hartnett develop on camera. “Chefs are the world’s worst communicators. It’s about getting them to slow down.”

Llewellyn says Ramsay’s restaurant experience of developing chefs is helping OPTP do likewise, but she does have concerns about the general quality and quantity of food shows. “A lot of cookery programmes have got quite cynical,” she says. “It feels like broadcasters and producers are doing them because they sell books and make money. I don’t want to slag anyone off but…”

Ramsay cuts in: “I mean Sophie Dahl, no disrespect, but I wouldn’t imagine…”

Llewellyn jumps back: “I thought that was better than some. But what annoys me is that I used to make arts

programmes, and you practically had to have three degrees to get on TV. There are people making food programmes now who know fuck all about food. That irritates me.”

Imitation irritation

Ramsay, unsurprisingly, can get irritated too, and claims he likes to measure OPTP’s success in terms of how many times its shows have been copied. “We don’t need to vent that,” he says, before going on to do just that. “It gets fucking frustrating. I mean, come on: Bar Rescue? Salon Rescue Nightmare?You can rescue a lot of things…”

Including, sometimes, people. Gordon Behind Bars was a departurefor the chef and moved him further towards the kind of social experiments that have become Jamie Oliver territory. He speaks about the series with great enthusiasm, even the 4.30am self-defence classes he took ahead of filming, and has a similar project lined up for next year.

“When you get used to MasterChef’s huge budgets and glossy sets, there’s something quite gratifying about doing a show in a prison,” he reflects. “My background dictates that I have to keep in touch with where it all started. It’s solace, I think. There are areas in my life and career - my little brother, his addiction. It could have flipped the other way.

“It’s also about silencing the critics, because the money’s filth. You get so much flak when things are successful, so much shit and such scrutiny - doing something like that is not about the money, because it’s raw.”

He gets animated at this point, speaking with an intensity that makes him more obviously recognisable as the Ramsay from his various shows. So is the Gordon Ramsay viewers see an exaggerated persona? Or is it a fair representation of how he genuinely is? Ramsay admits it’s very difficult to know, but his production partners are in no doubt. “It’s absolutely the real thing,” says Llewellyn.

Adler adds: “As we’ve got to know him better over the years, we do everything we can to reflect the real Gordon on telly. That means we can show that he can be funny, or get his kit off - we’re proud that he trusts us.”

Gordon Ramsay on…

Other food shows

“The success of Great British Bake Off is partly due to the economy, which has knocked the pomposity out of the TV industry and the restaurant industry. Great British Menu too is registering how good food is in Britain across Europe.”

Perceptions in the US

“The Americans think I grew up in Stratford next to Shakespeare, when actually it was the biggest shithole.”

TV experience

“I’m still learning about the TV industry, but I have no fear. Whether it’s fronting Cookalong Live or appearing on Have I Got News For You, where you’re going to get pummelled, I go in thick-skinned.”

Early days

“We’ve come a long way. I remember being on location for the first Kitchen Nightmares in the Lake District, and Pat doing the washing up while Ben was desperately trying to sort out the next location.”

No comments yet