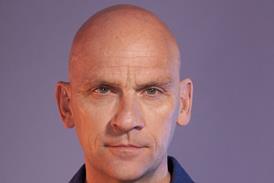

Broadcast heads to a former Dutch military base to hear about John de Mol’s plans to make a ‘more upscale Big Brother’

Over the past few weeks, execs from the biggest broadcasters in the world have made their way to a disused military base in the Dutch countryside.

Tucked away between the towns of Hilversum and Laren is what feels like a relic from the Eastern bloc or the setting for a horror movie, but is actually the home of the latest major format from John de Mol.

Utopia, a shift back to the idea of reality TV as social experiment, is a huge show. It has a production team of 160, airs five nights a week on Dutch channel SBS6 – which De Mol part owns – and is scheduled to run for a year. Not that that’s putting off potential buyers of the format.

“There’s only one factor that matters: is it a success or not?” says Talpa Media owner De Mol. “If it is, the broadcasters will come here like bees to honey. Especially when it is proven; when they can see the show and its ratings.”

Utopia only launched on 6 January but Fox in the US has already snapped it up (Simon Andreae bought the show last week) and De Mol says buyers are wasting no time. “The Voice was quick, but this was even quicker – we haven’t been on air for two-and-half weeks and we’re close to deals in several countries,” he says.

Gut feeling

He’s predictably tight-lipped about other territories, including the UK, but keen to discuss Utopia’s origin, which lay in De Mol’s “gut feeling” that, 14 years after Big Brother, the reality genre was due for a shake-up.

He explains: “Talpa isn’t an ordinary production company, it’s a creator of ideas. We do have a production division to make shows, but the whole company is based on creativity.”

De Mol has a team of around 25 people that work directly with him on format creation. They do so in a professional way, studying trend reports and what’s going on in the world, and meet on Monday nights to discuss what they’re thinking about.

“During 2013, we noticed a fairly constant piece of information: people are really insecure, they’re worried about their financial future, and they’re unhappy with regulations. So we asked ourselves: what happens if we give people the chance to do it all again? Would they be able to create a mini society rather than the one we are living in now?”

The emphasis on Utopia’s inhabitants shaping their society dovetails with a far less ‘produced’ format.

There are nomination structures and some duty-of-care rules, but De Mol describes it as a far “purer” show, with fewer “strings to pull” and no equivalent of Big Brother’s games and tasks. “In Big Brother, the fridge is filled every day, the people could just sit on the couch. Here, it’s cold and they have to create a heating system.”

The result is that arguments on Utopia tend to be about setting up a group hierarchy or agreeing how decisions are taken, rather than rows over who drank the last beer.

“It’s a more upscale reality show because the level of the people inside is slightly higher than for BB,” De Mol says. “Utopia genuinely has people who want to show the world that things can be done differently. Even so, if 15 people want to achieve something, the way they want to get there always creates arguments or different points of view. There are many decisions, and the process of getting to the answers is very exciting.”

The show also takes Big Brother’s back-stabbing out of the equation: the nominations process takes place in front of the whole group and each participant explains their reasons. “There’s no hidden agenda, no pretending to be best friends. It’s open and fair. We’re asking people to create the perfect world, so it makes sense to give them the chance to correct the group a little bit – to take out one rotten apple,” he says.

Production techniques

But while the production is hands-off in terms of influencing the inhabitants, it still requires plenty of hard work. The gallery is a frantic hive of directors and camera operators following storylines and loggers hammering in metadata details and taking notes of dialogue.

The editing is also more considered and crafted than Big Brother. Each episode of the latter features the previous day’s highlights, but Utopia has a five-day lag between real events appearing on the show. The delay, one senior production exec tells me, is because “we’re making a soap opera”.

That might explain why SBS airs Utopia at 7.30pm. It was conceived as a shoulder-peak show offering multiple repeats – there’s an 11.30pm repeat and more repeats in the morning and early afternoon the next day – although De Mol acknowledges international broadcasters might have their own view on when it should air.

What he will demand is a chance for Utopia to prove itself. He knows that a channel buying the format is unlikely to guarantee a year-long run, but Talpa will seek a minimum commitment of around three months to give the show a “fair chance” to prove its popularity.

If (or should that be when?) a UK broadcaster picks up the format, a decision will need to be made on which company will produce the show. More than 18 months ago, De Mol told Broadcast about his ambitions to establish Talpa UK, but there’s been little progress since, despite talks behind the scenes. “It’s still on the agenda,” he says. “Once we find the right partner or the right people to manage it, we’re ready to go.”

Is it something he is actively pursuing? “There were a lot of discussions in the past year about different strategic moves, and that made us a little reluctant. Things are still going on that make it a little difficult to start our company. In the next few months, we’ll decide which way to go.” What those “things” are isn’t clear.

Shine Group is Talpa’s joint venture partner in France and Australia, for example, which might be one option, but he also hints at a “bigger agreement with a larger player for a wider international rollout”.

Whichever route he goes down, there will be plenty of interest, not least as Talpa’s business model has been a factor in De Mol’s success over the years.

The company owns a third of SBS Broadcasting and uses its channels as a test ground for Talpa formats – De Mol calls it “fine-tuning” – which then reassures international broadcasters.

“There aren’t many companies capable of doing that,” he says. “They’d like to, but buying a substantial part of a broadcaster is a big step – and it only makes sense if, on the other side of the operation, you have the people to come up with the great ideas. If you only have one good idea, then it doesn’t work.

“The 25 people who work constantly with me to create formats and elements – that’s Talpa. Once we’ve created those formats, I want to make sure the execution is right. I want us to do that ourselves. But I’m not so much a producer – I’m a developer.”

Utopia: How The Format Works

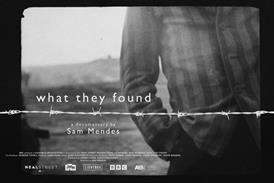

Utopia is Talpa Media’s attempt to bring some purity back to the reality genre – with viewer involvement ramped up via second screen and producer manipulation cut back.

The initial premise is that 15 participants aged 20 to 60 are selected to spend a year creating their own utopia, living in a leaky old silo on a disused military base.

They are given €10,000, two cows and a brood of chickens, plus a single mobile with €25 credit. They may take in a small crate of possessions, but must otherwise fend for themselves.

Friends and family visits are forbidden, but interaction with the outside world, in particular business deals, is allowed. Participants can use their cash to fi x the roof or the taps, but they also need to spend it on food, as the winter start means they can’t grow anything for the first three months.

The show’s website features a section called Doing Business with Utopia. Almost immediately, there were 2,500 proposals from Utopia ‘passport holders’ – viewers who pay €2.50 a month, which allows them to do business with the Utopians, watch four live streams and use two 360- degree cameras. A few weeks in, Talpa has sold 50,000 passports.

The nomination and eviction process is complex but, perversely, takes place in the open every four weeks. All 15 participants are given three points to allocate to their fellow Utopians, which can either be put against one person, or shared among several.

Passport holders collectively also have three points to allocate, based on their total votes.

The three highest point scorers are up for eviction. Meanwhile, passport holders select two from three candidates to go into Utopia as potential new participants. Four days later, the 15 originals pick one of the two to stay permanently, who must then decide which of the three high scorers they will replace.

The show builds towards naming a winner in the final week. Inhabitants, viewers and passport holders vote until just one person is left – and they take home the total earnings generated by Utopia.

UTOPIA: THE VIEW FROM HOLLAND

What’s Utopia like to watch? Painful and fascinating in equal measure, writes Netherlands-based journalist Lisa McDonald

Like all reality shows, Utopia hooks us in by appealing to our voyeuristic nature and our desire for drama.

Designed to be a real-life soap to rival Goede Tijden, Slechte Tijden (Good Times, Bad Times), Holland’s number one soap opera for 20 years, it features an array of larger-than-life characters, such as: Rienk, the suspiciously well-educated drifter and the only resident to grasp the project’s ideology; Billy, the ‘life artist’ whose whining ways grate on everyone’s nerves – including the cows, who won’t produce milk when she’s around; Emil, the burly professional wrestler who wept when confronted with too much tuna in his sandwich; and Jimmy, the menacing paramilitary giant who refuses to take off his red beret, sleeps outside in the shed, and is definitely not someone you would want to meet in a dark alley.

In the show’s current ‘storylines’, the residents are fighting over showers, food, chores and anything else that calls for decision-making or sharing.

The show is receiving a bashing on several Dutch websites about its authenticity (are some of these ‘real’ people actually actors?) but there’s no denying that real or not, you want more: more mediocre-quality video footage of gossiping girls milking cows; more alpha males fighting over food and asserting their authority; and more personalities clashing dramatically.

Critics also question the purity of the experiment, asking how residents can create a new society when they have frequent and daily contact with the outside world, including the internet.

Much of the debate has been intellectual in nature. What happens when people create a new society in a time of crisis, free from the perils of the world they leave behind? What changes?

Very little, it seems. Three weeks in, the participants are recreating the same old hierarchies and capitalist realities. It’s essentially survival of the fittest, with the strong and aggressive leading and manipulating the weak.

So will Utopia evolve into an idealistic micro-society that will revolutionise the way we think about our individualistic lifestyles and our political, social and economic systems – or is it merely a TV-dinner live soap with the added bonus of being able to evict unpalatable characters?

I’m hoping a bit of both, but fear that it will end up degenerating into the latter.

No comments yet