Having to abandon our original concept after gathering some incredible stories was a massive blow, but we were determined that wouldn’t be the end of it, says Iain Riddick

Production company Bigger Bang

Commissioner Tom Coveney (BBC); Beth Hoppe (PBS)

Length 6 x 60 minutes

TX 23 July, 9pm, BBC4

Executive producers: Ben Bowie; Iain Riddick

Directors Christopher Riley; Sean Smith; Nat Sharman; Nathan Williams

Series producer Tim Green

Post house Clear Cut Pictures

Distributor BBC Studios

Revolutions began over a beer in Vienna in December 2015. I had an idea for a series that would trace our greatest ideas and inventions back to their incredible origins. In doing so, it would tell the surprising and unexpected stories of the events that made the modern world: a leftfield take on the history of ideas.

We pitched it to Bill Gardner at PBS just before our flight home and he got it straight away. He could see, even in its nascent form, that it was rich and full of surprising and unexpected material. I’ve always judged a good idea or concept on whether it generates stories.

Stories should jump out at you – and that was the case with Origins, as it was called then. It was a story engine and, over that hour, we came up with countless ideas.

By the time my Bigger Bang co-founder Ben Bowie and I had reached Vienna airport, we’d chosen six subjects. By the time we landed in London, we had sketched out the basic framework of a six-part series.

We were in paid development by January 2016. We spent four months conducting extensive research, creating a sizzle reel and honing the stories into an 80-page treatment.

By late spring, the finance was in place and we expected production to start imminently. It was a gift of a series. Then, it hit the wall: we heard that National Geographic was also developing a series called Origins.

From what we could tell, it was very different, but the overarching concept – going back to a point of genesis – was close enough to take the shine off our idea. Worst of all, Nat Geo’s series was, by all accounts, about to start production. Our Origins series was dead.

We’d uncovered many incredible stories, but we no longer had films. Instead, we had fragments, so we began looking for other ways to piece them together into a new, unifying idea.

Over the next six months, we devised and pitched countless concepts to Beth Hoppe, then general manager of audience programming at PBS. Each time, she loved the content, but not the wrapping.

Finally, after several more months of meticulous research, we pitched the idea of building the series around six iconic objects: the smartphone, the telescope, the car, the robot, the rocket and the plane.

These objects weren’t invented in isolation, they are the culmination of a long-held human dream – to explore, to communicate or to find our place in the universe. They are familiar yet hidden within them are thousands of years of thought, struggle, determination and insight. The ‘object’ was our new, unifying device.

Beth green-lit the series on that verbal pitch and half a side of A4. BBC4 came on board a few months later, with the inimitable Jim Al-Khalili lined up to front its version.

Revolutions, as it is now called, was always an ambitious idea: we’d film across the world, recreate historic experiments, feature a chorus of expert communicators and broadcasters, and tell 10 or so astonishing stories in every film.

At its heart, it is a series about extraordinary individuals having incredible breakthrough ideas. It’s full of fantastical stories and we wanted viewers to experience these first-hand.

Director Ben Harding created an animation technique that combines drama, archive and visual effects. It freed us from drama’s normal restrictions, so we could go anywhere and do anything.

Iain Riddick - My tricks of the trade

-

The element of surprise is a film-maker’s greatest secret weapon.

- Good ideas are story generators.

- Believe in your idea and be persistent.

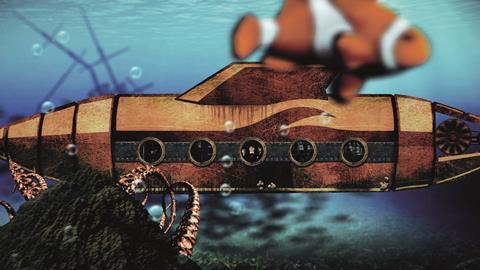

We recreate the first human flight in Scarborough. We follow Bertha Benz, whose legendary expedition transformed the car from a novelty item into something people wanted. We join Jules Verne’s epic adventures – journeying beneath the earth and the ocean and rocketing to the moon. There is tragedy, death and disaster, and moments of pure elation and joy.

The whole team worked incredibly hard and the results are stunning. However, using an object as our overarching concept gave us a final, unexpected challenge during the edit: it was too easy for the audience to predict where the film was going.

Despite such incredible stories, we’d lost the element of surprise. We began following leftfield turns, taking viewers in unexpected directions. Rediscovering those elements brought the films together.

Revolutions has been a true labour of love. The results are stunning, but most of all, the films are full of surprises.

ANYTHING GOES: HOW WE BUILT IMPOSSIBLE WORLDS

Ben Harding - series drama director

Whether scaling volcanoes, entering ancient Baghdad or travelling to the depths of the ocean, the fantastical stories in Revolutions are of epic proportions.

The scale of these stories suggests huge shoots with large crews and massive sets, but often this can result in lumbering behemoths that actually restrict the creative process. Instead, I developed a style that allowed for creative freedom, the ability to adapt and improvise and, importantly, gave time and space for the actors to flourish.

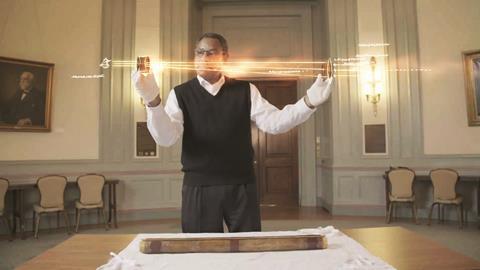

Shooting against green screen with just an assistant, we were able to work nimbly while also gaining the freedom to come up with ideas on the fly.

It was as much a workshop as it was a film set: armed with power tools, MDF, gallons of green paint and a can-do attitude, we had the freedom to create and build worlds that would otherwise have been impossible. To be able to conceive of an epic volcano climb and to be shooting 20 minutes later was an incredibly liberating process.

Shooting in 4K for a 1080p output allowed us to reframe and punch in during the composition. The actors were placed into ‘virtual sets’ built from hundreds of specially shot stills, which were layered up to give a sense of 3D space when the camera moves.

Again, freed from restrictions, we were able to play with sometimes impossible camera moves, dress the sets with dinosaur skulls, create magical lighting and, most importantly, be able to react instinctively to ideas.

If, instead of placing action in a stately home, I decided that our hero should be atop a cliff in a raging storm, we were free to enact this change in a short amount of time.

OVERCOMING OBSTACLES

The ability to attempt ideas that would normally be out of reach was a truly rare privilege. As film-makers, we strive to bring what’s in our minds onto the screen with as much clarity as possible, and this can be a painfully frustrating process.

In removing all barriers and obstacles that stand in the way of an idea, the making of the drama for Revolutions was a uniquely liberating and creatively freeing process.

No comments yet