Where other takes on the siege of Troy focus on the Greeks, this BBC1 version puts the Trojans centre stage. Gabriel Tate meets the producers

Production company Wild Mercury in association with Kudos

Commissioners Charlotte Moore (BBC); Elizabeth Bradley and Alex Sapot (Netflix)

Length 8 x 60 minutes

TX 17 February, BBC1

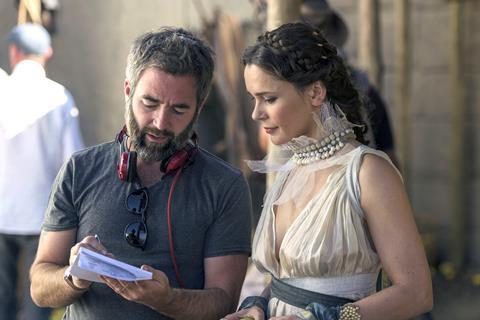

Executive producers Derek Wax (Wild Mercury), Christopher Aird (BBC); David Farr

Directors Owen Harris; Mark Brozel; John Strickland

Series producer Barney Reisz

Writers David Farr; Nancy Harris; Mika Watkins; Joe Barton

Production designer Rob Harris

Stunt coordinator Franz Spilhaus

As a means to put a fledgling production company on the map, adapting the oldest story ever told isn’t a bad idea.

Broadcast over eight episodes on BBC1, and streaming on Netflix internationally, Troy: Fall Of A City was the brainchild of former Kudos executive producer Derek Wax – and is the first show made by his indie Wild Mercury since it was set up in 2016.

Produced in association with Wax’s former employer – both companies are part of Endemol Shine Group – the idea came to him seven years ago, when he was on holiday in the Greek islands reading a book about mythology.

“We’d just finished Occupation,” he says, referring to Kudos’s Bafta-winning Iraq War drama.

“I thought: this is one of the oldest wars ever written about and there’s so much psychological complexity and dimension in these characters, though they’ve often been done in a cartoony, Saturday teatime kind of way. Could we find another way into their tragic moral dilemmas? Could this be done as a mainstream TV drama?”

Classical grounding

He approached David Farr prior to the latter’s adaptation of John Le Carre’s The Night Manager, and found a writer with his own grounding in the classical world.

“I’d done a theatre version of The Odyssey that had a strong Trojan angle to it,” says Farr.

“This is normally a Greek story, the story of the winners. I wanted to look at what life would be like in a city under siege, specifically for Paris and Helen, who had to live through that siege having caused it through an elopement – a mutual, crazy, reckless decision. Exploring that internal landscape of identity was fascinating. It’s an epic version of wrenching pain.”

Episodic television seemed the logical format to tell a multi-layered tale with so many big characters: David Threlfall’s Priam, Johnny Harris’s Agamemnon, Joseph Mawle’s Odysseus, David Gyasi’s Achilles, Jonas Armstrong’s Menelaus and Frances O’Connor’s Hecuba.

Wax consequently pushed hard for eight episodes rather than six, allowing time to establish Paris and Helen as central players rather than the mere catalysts they have tended to be in most previous versions – notably 2004 Hollywood blockbuster Troy. It also provided room to assess the impact of war on the citizens of Troy.

“Normally the war is decided through battles,” says Farr. “But for us, it’s also the emotional politics inside the city, which we had to invent. We keep the framework, the Homeric structure of Hector, Achilles and so on, but we’ve added an equally powerful internal narrative of intrigue and betrayal. Longform television allows you to settle the pace and really suits a story about a city.”

That city has been recreated in three locations around the South African cape: the palace interior in a Cape Town warehouse, the Lower City (home to the general population) in the northern district of Durbanville and the Upper City and courtyard in the shadow of the extraordinary Simonsberg Mountains.

Production designer Rob Harris, a veteran of South African productions since HBO’s Generation Kill a decade ago, worked closely with historical advisers Bettany Hughes and Nigel Tallis to ensure a degree of verisimilitude, but also the latitude to invent and adapt.

“I had my own army to get the sets ready,” he says. “We did a lot of research with the British and Ashmolean museums, but this supposedly took place in 1,300BC, so they didn’t know everything. As it’s open to interpretation, we’ve built from scratch, using a lot of informed guesswork based on the archaeology.

“Our techniques have been a mixture of ancient and modern. The architecture was simple on the outside and much more ornate on the inside, so we have murals in the palace based on those found from the era. We built the walls out of stone up to about three metres, then laid mud bricks on top of that, and plastered over it to keep the rain out.”

“You could argue that the storytelling in the 2004 film version suffered because they were so obsessed with the spectacle. We’ve tried to do the opposite”

Rob Harris, production designer

A Trojan breastplate hangs off a pole in the courtyard, its scaled effect a striking aesthetic contrast to the basic leather and bronze of the battle-hardened Greeks. A few dents are evidence of some vigorously physical battle scenes and, indeed, while some CGI was inevitable, producer Barney Reisz was keen not to rely on it.

“We would never have a shot where people would say, ‘that’s a great visual effect,’” says Harris. “It’s tricky, but we wanted to integrate it into the show. You could argue that the storytelling in the film version suffered because they were so obsessed with the spectacle, so we’ve tried to do the opposite.”

Not that the series stints on set-pieces (see box), thanks in part to the extra budget and greater ambition generated by Netflix’s involvement.

“Co-productions are the way of the world now,” says Reisz. “Netflix has been very supportive, with clear opinions, yet wonderfully hands-off with the creative team, which is sensible. If you pick the right people, it should more or less make itself.”

STAGING EPIC FIGHTS

Franz Spillhaus, stunt co-ordinator

I came on board Troy from Starz’ pirate series Black Sails, which was all swordwork. That’s a different kind of fi ghting, with different weapons, but the concepts and general mechanics are similar.

It was really important that each actor in Troy: Fall Of A City had a different fi ghting style. Achilles (David Gyasi) is all about speed and accuracy, Hector (Tom Weston-Jones) is more aggressive and grungey, Paris (Louis Hunter) is very fast and goes 140% into it.

The main cast have put in so much time and effort, and the results will be seen on screen. We didn’t really need to use doubles.

BRINGING OUT THE EMOTION

The Hector vs Achilles duel was a big one. It took four days to fi lm, partly because we needed to keep the sun in the right place, but also because we wanted to get into the emotion of it.

David is very methodical, which is perfect for Achilles; Tom just wants to go-go-go. It’s a long fight, with lots of different weapons – spears, shields and swords – so they could really show off their skills.

I planned the set-piece battles with specific spots in a lot of detail. The biggest one had around 200 extras and stunt people, plus eight chariots and 16 horses.

We had 40 stunt guys working on it for three days, blocking three or four different fights and training those extras who made it through boot camp so they could fight the same person all day, switching between being attacker and defender. It was good fun and looks fantastic – the series has been a blast to work on.

Reisz is braced for the comparisons that any epic series featuring sword fights and internecine political manoeuvrings faces. “I love Game Of Thrones,” he says.

“But it’s pure fantasy with monsters and a videogame sensibility. We’re doing a story a lot of people know already, with characters they will recognise. We’re trying to comment on human nature in the way Game Of Thrones does, but I think we dip a little deeper into human psychology.”

Provided Troy: Fall Of A City finds an audience, Farr is open to the idea of returning to the story.

“There are characters that survive,” he says. “And there are moral and emotional consequences of that survival that I would love to explore.”

No comments yet