The true crime producers discuss the unique pressures of working in the genre, competing for eyeballs with drama, and how social media is enriching storytelling

Sophie Jones

Executive producer at Minnow Films. Credits include BBC2’s The Detectives: Fighting Organised Crime and Catching A Predator, and upcoming Netflix doc Trust No One: The Hunt For The Crypto King. Sophie got her break as producer/director of Channel 4 First Cut film My Brother, The Murderer and has also worked on C4 staples 24 Hours In A&E, The Undateables and One Born Every Minute

John Smithson

Co-founder and creative director of Arrow Pictures. His latest series, I, Sniper: The Washington Killers, landed on Channel 4 in January. His many credits include C4’s A Year Of British Murder, HBO’s Thriller In Manilla, award-winning feature docs 127 Hours, Touching The Void and The Beckoning Silence, plus 9/11 docs The Falling Man and Phone Calls From The Towers

SOPHIE JONES I’ve just watched part one of I, Sniper. It’s chilling. Hearing his voice totally elevates it, doesn’t it? You can hear how cold he is in his answers: “It’s a person, it’s money. It’s a target.” There’s no emotion at all.

JOHN SMITHSON That’s what’s chilling. Lee Malvo is intelligent, articulate and thoughtful, yet he talks dispassionately about what he did.

SJ You lucked out with him.

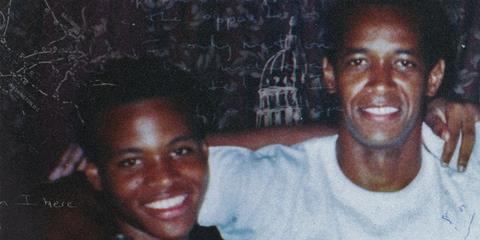

JS Very rarely, if ever, do you hear a voice like this: a 17-year-old who fell under the influence of an older man, who was killing people at random with an eerie cold-bloodedness.

After making contact, we had hour after hour of audio with this guy from his prison - he was allowed one call every two weeks. Accumulating 17 or 18 hours of audio over two years gave us the unique voice of a killer talking in chilling terms about what he did. And crucially, that helps us understand why he did it - this young kid, beaten by his mother, ignored by his father, falling under the influence of this 41-year-old man.

SJ Once you were weaving his voice throughout the narrative, you must have gone back and forth quite a bit in terms of how much to use it and whether you were glamorising it too much. Did you have those conversations consistently?

JS All the time. It’s a fine line between trying to tell a story and not exonerate him, while trying to understand him. We went back to his teachers to see how, just with a different roll of the dice, he would be a completely different person now, rather than spending the rest of his life in jail.

That’s why these things take a long time – we were in the edit for a year – because to get that right voice and tone is crucial. We risked the audience thinking we were trying to say, ‘Is this just a poor, misunderstood guy?’. But within the first two minutes, he talks about going up to a door and putting a gun to the head of a young girl with a baby crying upstairs, to prove himself to the older man. So it’s difficult to win sympathy.

“True crime takes us back to when we were kids - you’re in a land of good versus evil, and you always hope that good prevails and justice is served”

Sophie Jones

SJ You’re constantly walking a tightrope. On Catching A Predator, we went back and forth quite a lot. We had a huge responsibility to Reynhard Sinaga’s victims. A lot of them still hadn’t come forward as there is a stigma attached to male rape. Ultimately, further victims came forward, and further justice was brought. So it felt like there was a real purpose to why we were making that doc.

True crime takes us back to when we were kids - you’re in a land of good versus evil, and you always hope that good prevails and justice is served. You’re hoping that the end result is what everyone wants it to be.

JS Television’s a very powerful medium and using audio material can be particularly effective when you’re not distracted by seeing footage. You could just put that audio over archive shots of the crimes. Malvo was killing people at random and you just have to judge it in the cutting room. We obsessed on a daily basis about walking that line.

SJ One episode of The Detectives series three features a gangster who became a bit of a name. People were tweeting about him – he was, for want of a better word, a ‘perfect’ villain in that he actually spoke rather than simply saying “no comment”. When he spoke, he gave you an insight into this 6ft 5in beast of a man. That was one of the first times I saw on Twitter that people had this absolute outpouring of love for, and trust in, the police.

When you’re seeing the dogged determination of individuals showcased through a documentary, you’re able to really understand the lengths to which they go to get justice. And that starts to change a nation’s perspective of those fighting crime.

JS I remember feeling that when I first watched The Detectives, getting up close to those incredible characters. With factual doing so many big, high-quality, multi-part arcs, it’s become a circular relationship between the scripted and non-scripted worlds. It pushes the bar higher in terms of quality, the form, your whole creative approach. It’s a positive arms race and, fortunately, the budgets are available now.

SJ Totally, they borrow from each other. Watch the first 10 minutes of Line Of Duty and you could be watching the first 10 minutes of a police documentary.

JS All that obsession with detail in Line Of Duty – we are mutually benefiting from each other.

SJ It does surprise me sometimes that you can sit in a police interrogation and it will absolutely hold you. You don’t need anything else. There’s one camera in there, it’s not particularly pretty, you’ve got no DoP, somebody just hits record and that’s it.

“Drama has strengths that we don’t, but it’s not a competition. Docs just have to be good – a crime doc series has to be as nourishing as watching Happy Valley”

John Smithson

That’s where factual can trump drama because you’re dealing with real life. You want to see that person get interrogated – you want to see them crack, essentially, and admit what they’ve done. I don’t think you’ll ever beat that.

JS Drama has strengths that we don’t, but it’s not a competition. Docs just have to be good – a crime doc series has to be as nourishing as watching Happy Valley. We’re playing the same game, with the same rules. We’ve got to hook them.

SJ You’re totally right. You want to leave feeling as if you’ve just watched the best drama you’ve even seen.

JS Once upon a time, I, Sniper might have been commissioned as a 60- or 90-minute doc, but with so much material available from Malvo, it needed to be something else. I spent five years of my life on it and it’s one of the most difficult shows I’ve done, but the streamers’ appetite for crime has created a market that makes a six-part series like this achievable.

Finding a story is difficult in a very crowded market. Wikipedia’s ‘great British crimes’ entry must be its most accessed page in the UK. Everybody wants them but the bar is really high and the problems begin once you get the commission, because they’re really difficult to make. And guess what?

The broadcaster may end up never being able to show it – at least, not for a year or two. So for anyone thinking, ‘I’ll start knocking off a bit of crime because it’s a good area to work in’, it’s not quite as simple as that.

SJ It’s a creative nightmare, but that’s also the fun of it: to be able to take a story and work out the plot and all the twists – those rug-pulls that will keep an audience coming back.

JS You can’t just shove everything into the first hour - you’ve got to drip it in throughout. When we were about two-thirds of the way through making I, Sniper, one of the killers suddenly said, “I’ve got something to tell you”, and blew our minds with a revelation.

We use it to start episode four, which reflects the point in the story when we know about it. That’s what producing and directing is about: telling a story and feeding enough information through to the audience to keep their interest. But not overkill.

Devil in the detail

SJ With retrospectives, I always think you’re halfway there if you can bring the five senses alive. It all lies in the detail: what was the weather like? What did they eat for breakfast? They are pretty basic questions but it can really help set the scene. I think the more you can ignite people’s imaginations, and take them back to that point in time, the better. And sometimes, the more bonkers or bizarre the detail, the better.

“Everyone is living their life through social media platforms and, ultimately, that enriches our storytelling.”

Sophie Jones

Social media has helped hugely, and all the different archive resources that you’re able to bring along to storytelling. The quality you get out of a smart phone is exceptional now – it brings in a brilliant additional layer that we might not otherwise be able to access as documentary-makers.

That naturally draws a younger audience because they are suddenly seeing the kind of stuff they’re immersed in every day on Insta Stories, Facebook, Twitter and all of that. Everyone is living their life through social media platforms and, ultimately, that enriches our storytelling. Netflix’s American Murder: The Family Next Door showed you can make an entire film solely using social media posts.

JS It’s another gamechanger that we’re only now beginning to see the power of. For any event now, any crime scene, there is going to be so much material on people’s phones. It’s just a question of locating it, getting hold of it and working around the consent and legal issues of using it.

You don’t have a blank sheet of paper – you can’t just make the series you want to make, due to the legal editorial compliance framework that you have to work with. Once a crime gets into the legal process, there’s nothing you can do because of contempt of court – you have to sit on the programme until the accused has received a fair trial. I wonder how many films are sat on a shelf right now.

SJ We’re sitting on one – a three-part series of The Detectives filmed in 2018. We’re still waiting for it to go through court. Hopefully legals will go through in March.

Duty of care

JS So you’ve got all that, which is heavy duty, then you go through really stringent compliance processes. On I, Sniper, it took about six months – an elaborate process of going through virtually every word from interviews with 150 people.

SJ Rigorous duty of care and compliance is paramount. To make these series and push the bar creatively, we’re asking contributors to trust our team to come into their workplace or home. It’s their story, ultimately, and I always feel like we’re slightly on loan to it.

They’ve given us permission to tell it and we have to treat it with the respect it deserves, keep them informed and work with them, so they know what we’re doing with their story.

JS There’s a brilliant talent base now of young people who’ve been trained on some of these very difficult, high-compliance, super-sensitive crime shows. If they’ve worked on 24 Hours In Police Custody, or The Detectives, they know the importance of release forms, and they know about working with people in supersensitive environments.

Some of this new wave of directors and editors are doing quite brilliant work. True-crime is no longer regarded as a slightly sleazy tabloid backwater – get it right and you can be up for an award. You can’t get hold of a lot of the good talent, because they’re all working on a series for a year or 18 months.

SJ We’re dealing with a whole new pool of people that have come up on productions where legal, compliance and editorial have been treated as equally important. Go back 15 to 20 years and they were seen as something you only worried about at the end. It’s not like that any more.

From the very beginning, everyone’s on board, everyone has a set of protocols they’re working to, and everyone knows what they’re doing. All of that is done in conjunction with each other. And for me, that makes for a much richer programme.

No comments yet