Serena Davies on her nine-month odyssey to film penguins like never before

Production company: Talesmith

Commissioner: Janet Han Vissering

Length: 3 x 44 minutes

TX: 22 April, Disney+ (UK)

Executive producers: Ruth Roberts, Martin Williams, James Cameron, Maria Wilhelm, Pam Caragol

Series producer: Serena Davies

Line producer for Talesmith: Elisabeth Pinto

Editors: Stephen Moore, Gary Stephen Thomas, Kel McKeown, Darren Jonusas, John Freeburn

Producers: Heather Cruickshank, Bertie Gregory, Kim Butts

Field producers: Ross Kirby, Alex Ponniah, Ruth Peacey, Anthony Pyper, Andrew Graham Brown

Composer: Nainita Desai

Writers: Andy Mitchell, Serena Davies

Post-house: Halo

Penguins have ruled my life for two and a half years, and I still love them.

Natural-history filmmakers have long covered penguins, with National Geographic’s Oscar-winning March of the Penguins setting a high bar. Our production team was challenged to capture ambitious, never-before-seen behaviors and craft a compelling, original story.

The key lay in the details. We pored over research papers and worked with our scientific consultants to uncover the unexpected. One 30-year-old paper mentioned a hidden colony of African penguins on Namibia’s Skeleton coast. Another hinted that Galápagos penguins sometimes hunt together. These were the kinds of clues we were looking for.

For each of the three episodes of National Geographic’s Secrets of the Penguins, we created a wishlist of behaviours we hoped to capture with backups – then backups of the backups. Making the list a reality was another challenge entirely.

Penguins live in some of the most hostile and remote places on Earth. Most species live on the wild, uninhabited islands that dot the Southern Ocean, film-accessible only from live-aboard boats. Just reaching these locations required our crews to spend weeks at sea.

“We set our sights on capturing the moment when emperor chicks take their first swim, which happens just as the sea ice begins to melt - it’s hard to imagine a less suitable platform to film”

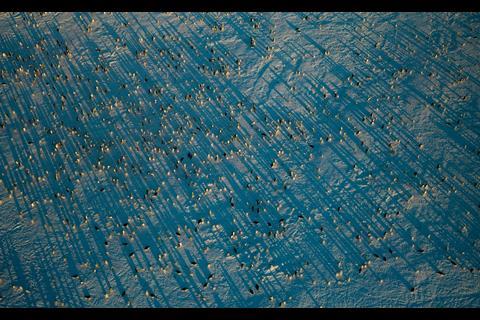

By far the most challenging species to film were the emperor penguins, which only live in Antarctica. Every year, as the sea around Antarctica freezes over, these emperors raise their chicks on a vast but temporary ice platform.

Early on, we set our sights on capturing the critical moment when emperor chicks take their first swim, which happens just as the sea ice begins to melt. It’s hard to imagine a less suitable platform to film. A wrong move could send the crew falling down a crack into the freezing water or – even more terrifying – leave them stuck on a large ice floe floating in the Southern Ocean.

Luckily, polar veteran Scott Webster and producer Heather Cruickshank devised a “Catastrophic Breakout Protocol” for such an occurrence, which represented just one part of our 100-page risk assessment.

Surviving an Antarctic winter

Filming the full lifecycle of the adults was an even greater mission: we needed a team to ‘overwinter’ in Antarctica.

Field producer Alex Ponniah, director of photography Pete McCowen and cinematographer Helen Hobin joined a team of nine scientists at the German Research Station Neumayer III. They spent more than eight months living and working together in isolation with no way in or out.

Enduring both physical and psychological feats, we set up a Starlink and created a bespoke data-crunching system to send the rushes back to London for editing.

While the logistics were challenging, we soon realised another issue developing: Penguins, apart from when they’re at sea, don’t do that much.

My tricks of the trade - Serena Davies

- Be open-minded. Know what you’re setting out to shoot, but be ready to pivot on location when unexpected stories evolve.

- Get everyone involved on board. Local fixers, guides and skippers possess a vast wealth of knowledge. Bringing them in on the process can unlock great stories.

- Involve your editor early. Logging and rough-cutting footage as soon as it comes in allows teams still in the field to receive feedback, adapt and improve in real time.

- Cut for emotion first. It’s easier to retrofit facts and exposition around an emotionally driven story than vice versa

Days and weeks could pass with what we dubbed “penguin mush” – endless shots of penguins just being penguins. But in natural-history filmmaking, things can turn around in an instant.

Seven weeks into our chick-fledging shoot, we had strong material but not quite the world-first behaviours. Extending the shoot was a gamble, both financially and logistically. The sea ice was becoming increasingly unstable, and keeping a team of 13 in a remote field camp was costly.

Days before they were due to leave, crew members, including National Geographic Explorer and wildlife cinematographer Bertie Gregory, spotted something incredible, topping our behavior wish list.

Hundreds of emperor chicks were spotted on the edge of a cliff. Nobody was certain what would happen next. When they jumped – and survived – we knew we had captured never-before-filmed and rarely witnessed behavior.

National Geographic released the clip a year prior to broadcast, and it now has more than 165 million social-media hits – becoming its most-viewed TikTok clip in history.

With 11 shoots in nine locations, we had amazing behaviours, but the heavy lifting would come in the edit. National Geographic’s ‘Secrets of’ format relies on character-driven moments throughout the films to provide unique insights into the species.

Lead editor Stephen Moore meticulously trawled through hundreds hours of footage spotting, collating and building the tiniest moments: a stumble, a squabble, and the wink of an eye from which he could weave a story.

We worked really closely with Janet Han Vissering and Pamela Caragol at Nat Geo on the creation of the series and ultimately what the final episodes would look like. They’re always great partners and their vision and feedback help elevate natural history storytelling in a bold, fresh way.

And Stephen and I spent almost 14 months in the offline looking at penguins all day, every day, and the miraculous thing is… I still love our penguin overlords!

Preparing for life in 50°C

Helen Hobin, wildlife cinematographer

For nine consecutive months, I lived and worked in Antarctica, braving extreme conditions to capture the resilience and community at the heart of emperor penguins.

Director of photography Pete McCowen, field producer Alex Ponniah and I joined nine ‘overwinterers’ at the German research station Neumayer III. Our journey and time there must be what it’s like going to and living in space – only with 12 people and 20,000 penguins.

Supported by our ‘Mission Control’ team at Talesmith, we breathed easy knowing we were in excellent hands.

There are no flights during the Antarctic winter, so we had no opportunity for replacements if anything broke. We invested in rigorous shoot prep, working with specialist technicians at kit facilities house Films@59 and testing out rigs in a -50°C freezer.

Filming in temperatures that dropped as low as -46.8°C, we used a lot of custom techniques. Pete and I each filmed on a RED V-Raptor VV with a Canon CN20 lens. We secured dovetail plates to the top and bottom of the rigs, quickly swapping between top-mounted and underslung whilst keeping cables rigidly in place. In the extreme cold, brittle cables can snap at the slightest bend.

We custom made polar covers, fitted with heating panels, to squeeze more life from the batteries and reduce ghosting on the monitors. Despite all these efforts, we often saw three ghostly versions of each penguin in the monitor. Harsh winds tried to freeze our eyes shut, and snowstorms erased orientation and the horizon. The cameras lived in custom foam-cut peli cases strapped onto our snowmobiles. We flew drones whilst wearing electrically heated paraglider gloves.

In the station workshop, we built small camera sleds onto snowboards. These allowed us to film the emperor penguins from the perspective of their chicks and quickly reposition by sliding the rigs. This became essential when curious photo-bombing penguins plonked themselves in front of the lens during critical moments, like egg hatching.

During the polar night—two months in which the sun doesn’t breach the horizon—we swapped the dynamic range and resolution of our REDs for the low-light capabilities of the Sony FX6. Watching the aurora australis dance over thousands of male penguins as they huddled and protected their precious eggs was a surreal moment in a wild, isolated place that had come to feel like home.

No comments yet