Director Erica Gornall unveils the expensive therapy process behind BBC2’s headline-grabbing doc

‘What’s the point of talking about the worst moment in my life and putting myself through this when he is dead?’

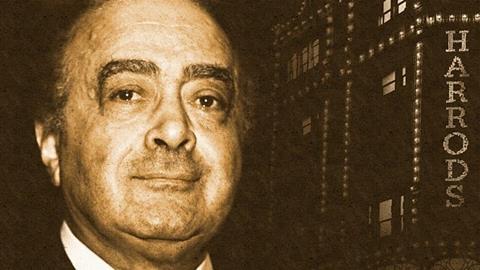

That was a common question asked during the first tentative meetings with the brave women who have now appeared in BBC2’s Al Fayed: Predator at Harrods.

I boarded this project in December last year, and it has been the most intense production of my career. An unprecedented number of survivors came on camera to allege serious sexual assault, attempted rape and rape, against their former boss Mohamed Al Fayed.

On my first day I was handed a dossier by Keaton Stone - a husband of a survivor and a brilliant director in his own right. He had amassed names of women spanning decades. Despite being an experienced filmmaker covering sexual and domestic abuse my jaw dropped at its magnitude.

Fayed died without facing nearly all of the allegations - which takes us back to those first conversations, in living rooms or the corner of cafes across the country: ‘What’s the point?’

It’s a good question. As filmmakers, indies developing films, and the broadcasters showing them, we should be asking very serious questions as to why we should be telling stories covering serious trauma.

It is a privilege to feature that testimony, and by the time we sit in front of victims we need to know the true purpose of asking them to come forward and speak out.

Like any group of women - we spoke to over 20 women and recorded 14 - the reasons behind wanting to speak out were varied. But one thing was consistent: they felt that this man had died with his legacy largely intact and they wanted to rewrite that drastically before it was too late, and he slipped from public consciousness.

The journey of those women throughout the production process was staggering. Some were keen from the start to appear on screen. Others did not want to at first, but over the course of months felt able to do so.

For others, the journey continued after transmission. One woman who only felt able to tell her story anonymously in the film lifted her anonymity last week during BBC Breakfast and is now openly talking about her experience. Another, who was raped but couldn’t give a statement to us before transmission, has now recounted her harrowing story to BBC News.

So how did we get here? It’s been the culmination of the skills and experience of my producer Cassie Cornish-Trestrail, the sensitive handling of executive producer Mike Radford, and the wider support of the BBC Current Affairs department who agreed to back one of the most complex films for duty of care I have come across.

After seeing the sheer number of women involved, I decided I wanted as many who felt able to talk to contribute. It’s a tough judgement call in storytelling terms - with fewer survivors I could tell more of their individual stories, versus more people but less testimony. With fewer, I could also dedicate more focus on supporting each woman.

“I also wanted to avoid having one woman take the burden of telling the entire story of an attack. Often, I had a few women take the story to the next stage, something which reassured many when they were viewing their sections”

Choosing to include so many women was, partly, because they wanted to be filmed - which highly unusual in this subject matter - but also to highlight the unambiguously prolific nature of Fayed.

It helped corroborate details in their stories, despite many not having known each other, and it showed that over the years, it was Al Fayed and his modus operandi that connected them all.

I also wanted to avoid having one woman take the burden of telling the entire story of an attack. Often, I had a few women take the story to the next stage, something which reassured many when they were viewing their sections.

With the ambition to have that many contributors must come the time and budget commitment to proper duty of care around each one, adapting as the numbers rise.

There was a lot to consider. Firstly, the team make-up was essential. In my experience, personal trust and communication is vital and, more importantly, make the production process less stressful for the victims.

I did not want these women to have multiple points of contact - they were with me and Cassie. This meant longer schedules, with more investment put in from the start.

Therapy sessions

Most of the women wanted independent support sessions with the therapist. But to get there and to do it right it takes a lot of time, money and support from those at the top.

The women had to feel listened to by an independent person not motivated to have the film go ahead – however nice we were. This need to be a priority.

I hear too many stories of it being done wrong - of producers taking on the unmanageable burdens of supporting contributors without professionals in place - severely affecting their mental health and causing the most conscientious people to consider leaving the industry.

The time spent by Cassie to source, talk to and brief the therapist, on top of liaising with each woman, was considerable. We had sessions for each survivor booked for after their interview, after viewing their interview during the edit, pre-transmission and post-transmission if needed. If you multiply that by the number of women in the film, that is a lot of sessions and financial outlay.

However, this process ensured that by transmission, and despite understandable nerves, all who filmed testimony of abuse were included in the doc.

Often the onus is on freelancers to push for more money, time and support in filming vulnerable contributors and traumatic subject matters. There are also stories of friction between production companies and broadcasters over therapy money and other support when producers are already overworked on tight schedules.

If there is only room for a short schedule, or there is no big conversation about duty of care from the start, you are not set up to make films with vulnerable contributors. I was lucky I had the BBC’s support and backing, but even then, we had to adapt significantly as the number of contributors grew.

There should be a clear mandate from above that these films have an extra tariff in place to make them well and with compassion. That is time and money and cannot be an afterthought.

One-on-one interviews

Cassie and I were the only team on location while filming. I was very particular that our producer - whomever that was - would also be a brilliant interviewer, as well as great with contributors. I shot nearly all the interviews on three cameras plus lights - something I have learned to do so that the whole interview can be conducted with minimal people in the room.

Often this is personal testimony hasn’t been said out loud to anyone, even family. My contributors told me our very small team was reassuring, despite the cameras. Cassie and I would plan the interviews together and our co-ordinator Charlie would help set up, but during the interviews it was one woman talking to Cassie.

I also decided to film a couple of people anonymously, allowing those who were not ready to be identified but who wanted to share their serious allegations to do so. I wanted this diversity of identification to make clear that every woman was valued in telling their story in the way they felt able.

A large part of why I believe those women felt supported was down to the doc being made by BBC Current Affairs. This unit, and exec producer Mike Radford, understood the impact of having so many women in the film, backing its ambition and the necessary expense.

I hope this top-down support becomes the norm. Contributors have the right to know that if they are in a film for any major broadcaster or streamer, they get a consistently safe experience. Duty of care should encapsulate mandatory training for any editorial and production staff considering making these films.

The reaction to the film has been overwhelming - both for those women and for the team with many of the women continuing to appear in their own right on TV and in the papers.

I hope that going forward I continue to work on projects that don’t just make it well at any cost, but make it right.

- Erica Gornall is a Bafta-nominated producer-director whose credits include Channel 4’s Who Is Ghislaine Maxwell? and BBC1’s Ambulance

Mike Radford, executive producer

The Al Fayed documentary is the third long-term investigation into allegations of rape and serious sexual assault that I have run in three years for BBC Current Affairs. The previous two were Tim Westwood: Abuse of Power/Hip Hop’s Darkest Secret (2022), and Andrew Tate: The Man Who Groomed The World? (2023).

A year ago this week, my current affairs colleagues at Panorama also produced The Abercrombie Guys. The massive impact of these stories is testament to the brilliance of the journalists involved but also to our determination to keep the subject of sexual abuse by the wealthy and powerful in the public eye.

These films are complex undertakings carrying significant legal risk. They are also expensive - Westwood took two years - and rightly require many safeguards to be put in place for vulnerable contributors.

Nor are they particularly commercial: neither Westwood or Al Fayed were picked up for wide international distribution, both considered largely UK stories.

Yet we have returned to this topic again and again. Why? Because powerful men need to be reminded that their misdeeds are increasingly difficult to keep secret forever. These are stories that need to be told, voices that need to be heard, justice that needs to be done. Al Fayed managed to die without facing that justice, hopefully this won’t always be the case.

No comments yet