The BBC’s commissioning editor for science and natural history is investing in developing programmes that will take viewers on an unexpected journey.

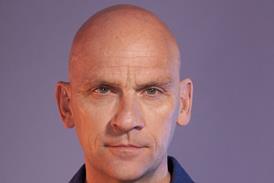

For someone who is virtually a BBC lifer, Kim Shillinglaw is refreshingly open about her employer. The things that wind up the corporation’s suppliers – the excess of red tape and its defensive approach towards its critics, for example – get under her skin as well.

The amount of time currently being spent on an internal restructure, and the impact it could have on screen, is also a worry. “Any interregnum can affect content, and I do have a concern that the BBC is spending a lot of time moving around the internal furniture,” she says. “The sooner it is resolved, the better; then we can all get on with doing what we should be doing.”

Shillinglaw even sticks her head above the parapet when it comes to Broadcast’s campaign to get more women experts on screen, offering a far less equivocal stance than the BBC.

She agrees it is true – “it’s a bad truth, but it’s a truth nonetheless” – that it remains difficult to source women experts when men dominate the upper echelons of science, but insists that it is the BBC’s duty to attempt to do so whenever possible.

“I remember on one of our Bang Goes the Theory roadshows, a girl of 15 came up to say thanks, and that she loved presenter Liz Bonnin so much she had changed her role model from Cheryl Cole to Liz. With no disrespect to Cheryl, I think that is just brilliant. If we can do that, of course we have a responsibility to get more women experts on screen. No question.”

And her honesty extends to her briefing from the BBC press team prior to the interview. “I’ve been told I can swear only once – I’m on strict rations,” she says – although, despite her best efforts, she exceeds that limit during the course of the interview.

But while she is under no illusions about the limitations of the BBC, Shillinglaw is obviously passionate about programme-making, enthusing about everything from The Voice to the potential of 3D, responsibility for which she took on last year. Her main role – commissioning 200 hours of science and natural history programming – also fires her up.

Top of Shillinglaw’s checklist is technical innovation. She highlights the recent BBC1 series Earth Flight, which gave viewers a literal birds-eye view of the world, and the forthcoming Miniature Britain, which uses state-of-the-art microscopes to uncover tiny details of the natural world, as good examples of the type of programming in which she is interested.

“Something that lets us show the viewer something that makes them think ‘I haven’t seen the world like that before’,” she explains. “Things that will reach out beyond those with a disposition for natural history, to people who are there to be entertained.”

Shillinglaw is the first to admit that science and natural history are not always the sexiest of subjects – “we have to shout louder to be heard,” she says – but notes the interest that the controllers have in getting them onto their channels.

They all have different approaches: for BBC1 boss Danny Cohen, it’s about scale and scope; while BBC2 head Janice Hadlow is after programming that takes the discussion further. But Shillinglaw is confident in the value the genre adds to a channel.

Her confidence is borne out by the stats. BBC1’s Frozen Planet was one of the highest-rating programmes of last year, averaging 7.99 million viewers (27.4%), while the stripped three-part series Stargazing Live secured BBC2 an average of 3.4 million (13%) earlier this year.

“I’m not sitting here worrying about science’s place in the ecology of channels,” she says. “I am sitting here thinking ‘we have less money, the media landscape is crowded, we do have to work harder to make what we do cut through’, and that is why I am so passionate about innovation in science output. We are really restless in looking for the next new thing.”

To do that, Shillinglaw is putting her money where her mouth is. The department has “money to spend on development”, and she encourages indies to approach her with ideas. However, she says she is keen to “get into more involved conversations with slightly fewer suppliers”.

She adds: “They are not off-the-shelf ideas. It does take a long time to get from the concept to the screen. But I recognise that the indie sector doesn’t have huge standing armies of development people, so we could do more to help them at that stage. I would love to have more pitches from the independent sector.”

There are slots on all three channels for which Shillinglaw commissions, but she says her priority is BBC1, where there is plenty of cash available. For the 9pm slot, Shillinglaw is on the lookout for programmes with “scale, wonder, maybe something using technology to see the world in a different way. Something with real impact”.

Meanwhile, the channel’s 8pm slot is calling out for “warm, humorous, relevant” shows, in the vein of Cherry Healey-fronted Britain’s Favourite Supermarket Foods.

Both BBC1 and BBC2 could benefit from an innovative medical or health series, and Shillinglaw says she is keen to do more with the magazine format, following on from the Star-gazing Live spin-off Back To Earth. She is also interested in “precinct” shows – such as After Life: The Science Of Decay or the recently commissioned Operation Iceberg, in which the crew will live on a “great big fuck-off iceberg” from the point at which it detaches from a glacier until it melts away. “It’s more the approach than the subject that I’m interested in,” Shillinglaw adds.

One of the many rumours fuelled by the year-long Delivering Quality First process was that science would be cut disproportionately from BBC4, leading fans of some of the more in-depth pieces of programming to accuse the corporation of dumbing down. But now the process is grinding towards a conclusion, it appears the genre will still have a place on the channel. While its budget will be cut by more than that of most other factual genres, it has been less hard hit than history, which is coming off the channel completely.

Although she admits the decision happened “well above my pay grade”, Shillinglaw believes this change of heart is partly as a result of the success of science on BBC4, citing shows as varied as After Life, the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures and The Joy Of Stats as examples of the breadth on offer.

“I’m really proud of how we have managed to get science distinct and separate on BBC1, BBC2 and BBC4. Science does require an act of trans-lation, and it is completely different between channels. That’s why there is a reason for it staying on BBC4. I’m absolutely effing delighted.”

Shillinglaw on…

Frozen Planet fakery claims

“We will always listen if there is more we need to do to keep an audience informed about how we make programmes. But our self-interested critics have to accept there was no malice, there was no intent to deceive in what the programme-makers did – and that it was an amazing programme.”

3D

“It’s very important to experiment around 3D. It could tank, it could take off, we just don’t know. Personally, I’m agnostic.”

The next DG

“The big challenge will be to continue to articulate a really strong narrative for the BBC and its purpose at the heart of British life. People have a strong intuitive sense, but there are times when we are less successful at articulating it. Any organisation needs that, and from the top, so that will be a key thing for the next incumbent to get right.”

Competition

“C4 and Sky are increasing their spend on content, and Peter Fincham is providing a strong creative leadership at ITV. Google is getting into content as well. I don’t think anyone is producing better content than us at the moment – but they are significant competitive threats. Competition is a good thing but we have to be revving on all cylinders.”

Fact File

Career

- 2009-present: commissioning editor for science and natural history, BBC;

- 2006-2009: executive producer, BBC London Factual and CBBC indie commissioner;

- 1990-2006: researcher, rising to series producer at Observer Films, then BBC London Factual.

No comments yet